Jeannine Tang

Penal Code and Monochrome: Notes on the Pink Dot

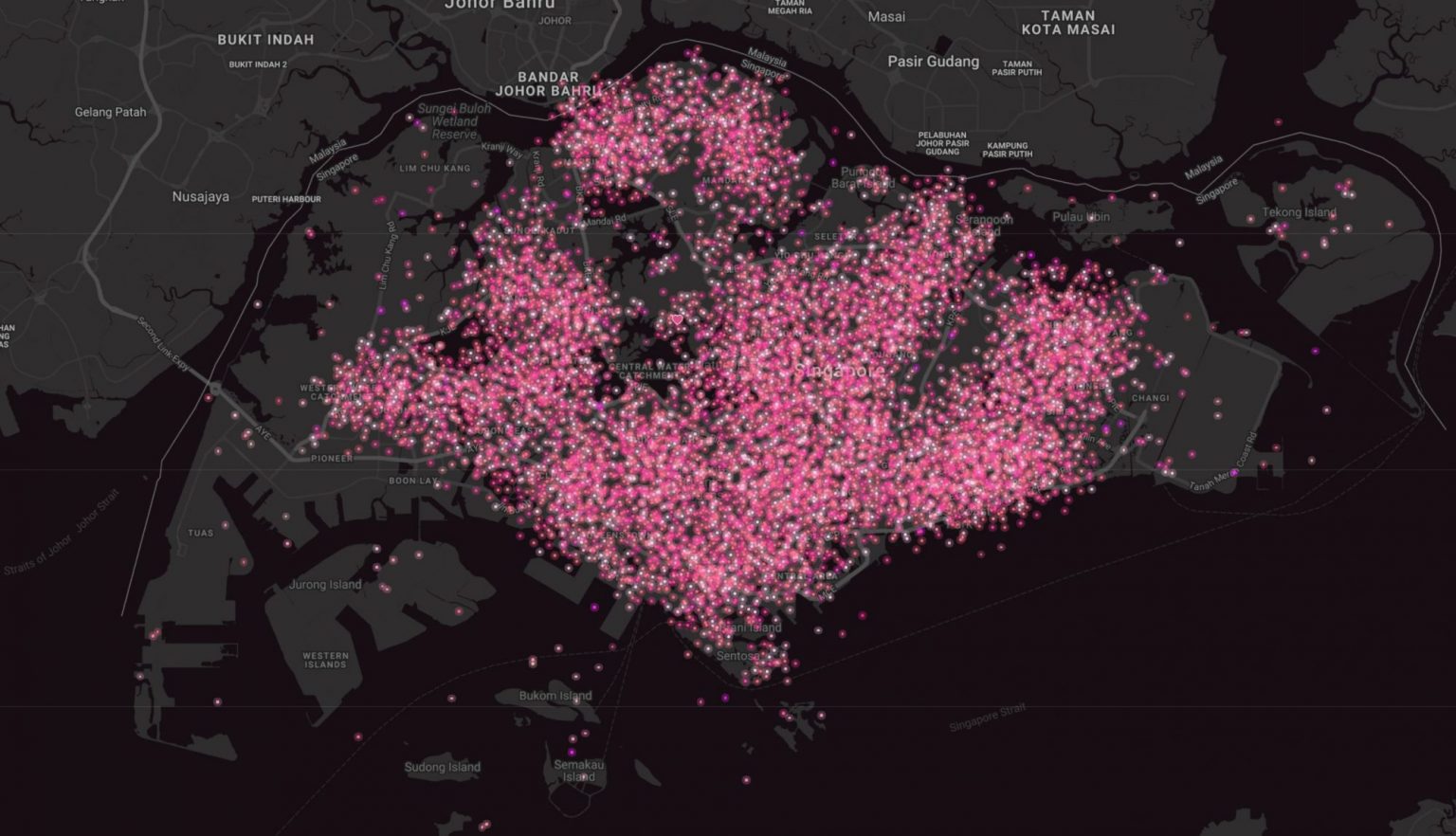

Pink Dot, aerial view of the “Repeal 377A” light-up at night in Hong Lim Park in 2019. Pink Dot SG

Pink Dot, aerial view of the “Repeal 377A” light-up at night in Hong Lim Park in 2019. Pink Dot SGIn 2008, a group of artists and designers produced Pinkie: a plush, round creature with a smiley face, rendered in a palette of pink hues (figure 1). Pinkie was an early visual emblem of the “Pink Dot” movement in Singapore, the most visually prominent and affirming symbol of struggles against state-sanctioned homophobia and civil society’s advocacy of LGBTQ rights. In 2009, organizers mobilized LGBTQ people, their given and chosen families, friends and allies to wear pink clothing, bring props and other pink-themed materials to Hong Lim Park, the only outdoor public space to permit public speech, demonstrations, and rallies at its Speakers’ Corner without a government-approved license (so long as race and religion are not discussed) since 2008.1 From this first gathering, the movement has grown from a following of 2,500 people to over 25,000 in less than ten years. As its visual signifier, Pinkie is ambiguously gendered and uses no pronouns; the strategic anthropomorphism of a pink dot was conceived in the branding vernacular of a logo and the physical manifestation of a mascot. Following Singapore’s independence from British colonial rule in 1963 and sovereignty as a nation in 1965, many public service announcements were embodied and voiced by state-designed mascots.2 In this tradition, Pinkie’s utterances extend another kind of national and collective voice, anthropomorphizing a movement whose annual acts of spatial occupation are captured from aerial perspectives as an iconic pink circle.

When gathering to form this shape, participants engage in the performative act of queerly imagining another kind of national belonging. If every figure appears against a ground, the history of the Pink Dot appears against the “red dot” so often used by local Singaporeans to designate or picture their country in relation to the world and her neighbors.3 While the fifty-kilometer length of this city-state-nation typically appears as a circular speck on countless world maps and spinning globes, the country was first described as a “little red dot” in 1998 by the then-Indonesian President B. J. Habibie, whose ascension to office received a lukewarm reception by the Singaporean government. (Habibie would also describe Singapore as a “little red dot” in comparison to Indonesia’s spread of green on a map).4 In patriotic, indignant response to this belittling of their country’s significance, Singaporeans resignified Habibie’s pejorative figure of speech, and “little red dot” has since been commonly used as an affectionate local self-description, given that the color also aligns with those of the national flag. Such chromatic nationalisms are referenced by the Pink Dot movement, across the flag’s two colors, the bubblegum pink of the country’s national identity card for Singapore citizens, and the linguistic geometry of the country as it has been mapped, described, and imagined. And so, Pink Dot’s monochromatic design strategy of pink circles and spheres—which includes shooting aerial photographs of pink-clad masses occupying public space with participants directing their bodies, props, and lights towards the camera above—forms not just any pink dot but the Pink Dot: a symbol of nation upon the ground of the governmental image.

Over the past ten years, the Pink Dot—as an event and monochrome visual iconography—has produced a changing sense of imagined community. The Pink Dot has been widely analyzed over the past decade through various legal, activist, and linguistic perspectives. To these approaches, I offer a reading of the Pink Dot’s photographic and visual culture. In doing so, this essay maps the trajectory of its social gradient on the ground to pictures taken from above, following the Dot across physical, aerial, and digital spheres to examine the effect of its monochrome, both on and between bodies, as it moves queerly upon the ground of the state.5

***

The Pink Dot’s annual gatherings were not, at their inception, overtly positioned as protests. Attendees seemed more likely to picnic than march, and the language of the event remains, as the organizers put it, an “un-Pride,” intended to draw the involvement of a population adverse to protest demonstrations and cultural expressions of anger and aggression. The organizers’ linguistic opacity regarding an otherwise striking and marked social form has been understandably rooted in the authoritarian nation’s absence of legal and civil protection for expressive freedoms, such as political demonstrations and rallies more typical of liberal democracies.6 As a result, the sphere of large-scale public gatherings in Singapore are commandeered by the state and controlled by the country's penal code introduced by the colonial British administration, which criminalizes assemblies of more than five persons. In light of this juridical inheritance, Pink Dot organizers have strategically understood that crowds are far more likely to form, or even set foot in the park—let alone contemplate joining a movement—if the genre of public gathering is convivial, and if public messaging moved through solicitous affect rather than antagonistic rhetoric.

Even as Pink Dot centers lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, and transgender people, the organizers also sought out allies from its inception, calling upon local actors, playwrights, comedians, and public personalities to act as spokespersons and ambassadors in public-facing videos and photographs. Consequently, the movement’s positive affect and family-friendly practices have been described as “homonationalist” and “homonormative.”7 These critiques are not irrelevant when examining the movement’s reference to the “pink dollar,” from its rhetoric of national unity, downplaying of sex to emphasize love, and careful alignment with traditional Asian values, including interfamilial relations within extended family units.8 That said, scholars such as Michelle M. Lazar describe Pink Dot’s “homonationalistic sensibility” as “aspirational politics” and “a mode of doing “pragmatic resistance,” echoing Yvonne Chua’s account of how gay social movements in Singapore “endure under the watchful eyes of an authoritarian government.”9 Not only does Pink Dot operate within an authoritarian rather than liberal democratic framework, but Singapore’s legal governance has also retained key sections of the British penal code that restricts both democratic public assembly and queer sexuality, the latter under section 377A through the explicit criminalization of anal sex between consenting men.

While many former British colonies have repealed this particular sodomy law following their independence from colonial rule, Singapore remains one of several postcolonial nation-states that retain the penal code through a justification of social mores, traditional values, and “natural” family formations (which consequently erases histories of precolonial homosociality and alternate forms of kinship).10 In this context, where activists are met with conservative community opposition and cannot fall back on democratic protections when challenging anti-queer legislation and social practices, certain resistance strategies bear heightened risk. Chua observes that activists avoid direct state confrontation and illegal activities, shifting strategies and tactics along a spectrum of “covert-overt” forms of action required to “achieve social change under authoritarian conditions.”11 The emergence of the Pink Dot notably followed the 2007 parliamentary debates regarding the repeal of 377A. Although that decision failed to bring about legal transformation, it should be noted that social movements rarely adhere to the case timelines of legal campaigns. Pink Dot has not only produced the most visible iconography of the repeal of this code, the movement also performs and sustains the political imaginary of repeal through its social practice and visual design.12

The pink cornerstone of the Pink Dot’s branding of public intimacy—a term I use to underscore the advertising and design backgrounds of organizers at the movement’s inception—has consistently associated itself with genres of tonal positivity and rhetorical uplift found in popular cultures. The language of rounded shapes, sans serif typefaces, and plush pastel mascots communicate friendliness and cuteness in a country where Japanese kawaii and other adorable aesthetics are commonplace. A gentle scrappiness also undergirds Pink Dot’s graphic design: rather than highly polished advertorial languages, the use of typefaces and letter styles references stenciled, guerilla graphic arts that seek to communicate in a more populist vernacular. This implies a grassroots collective of individuals coming together. Pink Dot’s graphic identity is intentionally disarming, while its social organizing gatherings at Hong Lim Park are assiduously solicitous and hospitable to all members of society: children, elders, and families.

The resulting picture shows intergenerational and intersocial picture of bonds between queer chosen families and traditional extended families, appealing to ethnic Chinese, Malay, and Indian cultures that comprise the majority of Singapore’s population, and whose traditional performances were featured in Pink Dot’s inaugural gathering. Scanning footage and photographs of past events of thousands of people clad in pink, it is impossible to guess who is gay, straight, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (as if one ever could), as differences are smoothed over rather than emphasized by the aerial vantage. From the outset, Pink Dot organizers sought this perspective of a human pink dot as a marker of social unity, photographing those assembled from a high window in a nearby hotel, prior to the availability of drone technology that was used in later gatherings (figures 2 & 3). Movement organizers aimed to grow the dot’s physical span every year, symbolizing society’s growing acceptance of LGBTQ people, and fill the park within a decade, a goal felicitously achieved by Pink Dot’s third gathering in 2012.

To the Singaporean government’s ongoing argument that society is not ready to decriminalize and repeal 377A, the formation of this pink populist image of civil unity provides a visual assertion that society is increasingly in support of change. That said, who can safely belong to this national unity has been a recurring question posed in many ways. With a sizable contingent of attendees not comfortable with being photographed, organizers developed protocols for their visual safety—a necessity given that Pink Dot images are made for viral dissemination.13 Other exclusions are not borne of individual volition but concern legal boundaries in Singapore’s social structure that differentially distribute freedoms and rights through citizenship. During the event’s early years, noncitizens could assemble at the park but were only permitted to observe from the sidelines.14 However, as the event’s popularity steadily grew—from 2,000 attendees in 2009 to over 28,000 people in 2015—the government introduced a Public Order Act in 2009 that was updated in November 2016, the revision stipulating that only Singaporeans and permanent residents could assemble in support of causes at Speakers’ Corner, affecting who was allowed in the park during the 2017 edition. Upon consultation with their legal team, Pink Dot organizers were compelled to check IDs at the entrance (figures 4 & 5).15

These legal restrictions received a physical analog: Pink Dot negotiated with the authorities, who required organizers to propose security measures for approval. However, all initial propositions were rejected and the organizers soon realized that the event would not move forward unless barricades to control entry were used along the perimeter of the park.16 The organizers were concerned that attendees would feel psychologically circumscribed and be physically hemmed into an otherwise open park, and fundamentally disagreed with the government’s restriction of entry to Singapore citizens and Permanent Residents. They also believed that noncitizen residents had the right to weigh in on issues foregrounded by Pink Dot, and that persons, families, and kin of different and mixed-citizenship were impacted by LGBTQ+ discrimination. And so, while Pink Dot organizers initially refused these terms, they acquiesced upon realizing that the event would not otherwise move ahead. At the same time, the homophobic backlash against the Pink Dot movement meant that organizers also had to take seriously growing concerns for the safety of their participants.

Organizers grappled with how the rhetoric of traditional Asian family values continues to be socially wielded, particularly by local Christian organizations influenced by U.S. conservative religious movements, such as the waging of “wear white” campaigns to uphold “pro-natural family values” in opposition to Pink Dot.17 This opposition emphasized a color often used by many faiths to symbolize purity and allude to the white dress worn in official appearances by Singapore’s ruling political party—the People’s Action Party—that has governed the country since independence in 1965, to signify incorruptibility to the public. Pink Dot organizers were worried about potential counter-protests by these groups and the possibility of vehicles being driven into attendees at the park, compounded by the lack of easy dispersal. To comply with legal restrictions and protect participants from potentially lethal threats, concrete block barriers were installed for the 2017 edition. Participants responded to these barriers from inside and outside of the park, holding hands around the barriers, while a local organization Oogachaga dropped a banner over them that read: “Bridges Not Barricades.”18 Various queer counterpublics enveloped the barricades, expanding the perimeter of the dot beyond the park itself. Their participation retrieved the social ownership of the event, while extended the act of gathering and assembly beyond spaces predetermined by the state.19

Over the years, Pink Dot has spread beyond state-controlled perimeters, giving its iconic picture of collective unity a diffuse rather than bounded life. Pink Dot is often an experience of and in movement, beginning well before anyone’s arrival at the park. Most people travel to the park by bus or train and so public transportation infrastructures are full of pink on the day of the event, as the spread of pink-clad bodies across quotidian space and time exceeds the physical site and time of the assembly. Pink Dot was also, from its inception, a digital image. Aware that the state-controlled press, television networks, and periodicals would not favorably publicize or report on the event, organizers launched their campaign through a dedicated website, as well as aggregated YouTube videos and social media participation on Friendster, Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.20

Although Pink Dot has spawned international iterations, and its influential digital images and videos move through transnational media flows, its dispersal retains a focus on combating LGBTQ+ discriminization—which includes decriminalizing homosexual relations—within the country, rather than the production of a general theory of gay rights.21 The organizers’ use of a monochrome visual strategy has been taken up by other social movements–for instance, recent climate change campaigns have formed a “green dot,” taking a leaf from Pink Dot’s visual playbook.22 Pink Dot’s chromatic choice was intentional: distinguishing the movement from the rainbow hues typical of international gay pride parades, often rhetorically blamed by conservative locals and the government as destructive, Westernized forces infringing upon Asian customs and traditional values. In its early years, Pink Dot received international attention and open support from corporate sponsors, such as Twitter, Bloomberg, and Google, and banks such as Barclays and Goldman Sachs. Press in the early 2010s observed this neoliberal corporate cultivation of the “pink dollar,” as real-estate developers, banks, leisure, and entertainment industries targeted a wealthy urban LGBTQ demographic in Southeast Asian cities.23 After the 2016 Pink Dot, these forms of financial and social support were publicly reprimanded by government representatives, who positioned such forms of multinational sponsorship as foreign intrusions that disrespected local cultures.24

As a result, Pink Dot turned to local organizations and businesses for sponsorship and support, and has been extremely successful in this effort, with the number and range of organizations growing every year. Paradoxically, in the wake of the United Nations Human Rights Council review of Singapore's record on homosexuality, the Singapore government argued that the very existence of Pink Dot illustrated that the government “does not tolerate violence, abuse, discrimination, and harassment” against any person or community here.”25 Critics such as Audrey Yue and others note that the government has, with Pink Dot’s growing following, come to claim the movement as an example of political acceptance of homosexuality, while banning books depicting same-sex relationships in the same year. Pink Dot’s counterpublic figuring of national unity—like all such efforts—are vulnerable to co-option by the state, and such delineations are always drawn upon a ground of social antagonisms, spatial evictions, and exclusion from sight and speech.

The pink light that illuminates Pink Dot and its changing perimeter also redraws what constitutes the inside and outside of its constructed sphere of unity. Scholars have noted how the assimilationist tendencies in the event’s organization have—at times—marginalized certain identity formations and social practices. Yue and Leung note that, “Pink Dot’s celebration of mainstream homosexuality (championed through the homonormative ideals of family values and family inclusion) also surfaces as a site of exclusion for other LGBTs othered by its normalising logic,” a logic which excludes or vets the messages of transgender participants.26 Regarding the different plaintiffs who have stood before Singapore’s judiciary as representatives of the case for repeal, George B. Radics points out how Pink Dot has embraced, as flag-bearers for the repeal of 377A, “two filial, educated, and ‘discreet’ men in a committed and loving relationship” while occluding a plaintiff criminalized for public sex.27 Indeed, the embraced political subjects of Pink Dot unevenly challenge as well as retain normative codes of class, race, and sexual behaviors that structure absences and exclusions within Pink Dot’s prefigurative politics of spatial presence. As the poet, playwright, and critic Alfian Sa’at has pointed out, even as organizers work to provide a hospitable atmosphere and accessibility for seniors and disabled people, “any embrace will come up short at some point because an arm span is finite.” Sa’at suggests that this embrace leads him to think about

the limits of inclusivity, the dangers of fantasising about utopian spaces, or spaces that aspire to speak for the entire community. In that anxiety to pack in bodies at the event, so as to create an optics of the local-indigenous, is bodily participation privileged over other forms of support? Be there or be square, be there or betray?28

Against pious defenses of Pink Dot, Sa’at argues for thinking of the movement “as part of something larger—and not as some large reservoir where other tributaries (no matter how many booths, how many representatives) are supposed to converge.”29 Indeed, we might recognize the value of Pink Dot not only as a provisional and changing picture of unity, but as a tributary, a vector, or an image whose life is potentially more promiscuous than the rhetoric of its production; could its image be taken up differently by those who look upon the park, travel in pink outside of it, work on or expand Pink Dot’s goals in less-than-visible ways?30 Organizations whose involvement was deterred, or when involved, had their messages vetted in early years (to include organizations working on HIV/AIDS and sex work) have either joined or grown their participation on their own terms, while Pink Dot has expanded its focus from coming-out narratives and repeal efforts, to providing a platform that frontlines the work of transgender people, sex workers, and people living with HIV/AIDS.31 This is to say: Pink Dot is a directed movement that is also redirected by others, and like all social movements that endure, the Pink Dot has changed through circumstance.

Across 2020 and 2021 it became unfeasible to gather in Hong Lim Park due to public-health restrictions on public gatherings owing to the Covid-19 pandemic, violations of which were criminal offenses punishable by fines, incarceration, and/or deportation. In a country where protectiveness toward vulnerable elders is a norm, these concerns were felt widely. As a result, in June 2021, Pink Dot took a different strategy: producing a digital map for which participants could drop a digital pin, mark their neighborhood or general location, and share a message of support publicly or anonymously (figure 6). Pink Dot also promoted strings of pink fairy lights for purchase at modest prices for people to light-up residences, businesses, workplaces, or spaces of gathering, and programmed a livestream with an extensive array of speakers, organizations, and participants. Since 2012 Pink Dot had turned its afternoon assemblies into evening events in a bid to avoid the 90F mid-afternoon heat of gathering outdoors. Using flashlights modified with tinted cellophane, this “lightup” of collective pink beams lit up the park for a sundown aerial shot.32

In 2021, this lightup spread out further across the nation-state. As Pink Dot’s COVID-19 edition solicited local organizations and businesses to join the effort, organizers avoided restrictive branding guidelines and intellectual property, offering the fairy lights and a public domain framework featuring an open-source red ribbon that could be improvised and adapted. These efforts encouraged the virality of the Pink Dot well beyond the organizers’ control or expectations. Using online digital networks—not only to promote but to organize the event—Pink Dot afforded the participation of young people and noncitizens as imagined and physical community, as well as identified local neighbors, businesses, and participants nearby, mitigating the isolation and segregation that are part of the spatial distribution of homophobia. In this way, pink light—previously contained by the barricades erected around the park and enforced through laws against public assembly33—exceeded the space of the park and the state’s allotted forum for public speech. This new tradition will likely persist and evolve, as such rituals do, when gatherings at the park resume.

We might recognize the physical and digital spread of the Pink Dot’s gradient as a monochrome against the penal code, or as a vector of movement amidst the ongoing, messy, and unfinished business decolonizing the British Empire’s techniques of sexual control and residual effects of anti-queer sentiments amongst postcolonial nationalisms.34 Pink Dot’s viral visual strategy has produced a model of unprecedented public assembly by intimate counterpublics. While contradictory in their politics, these assemblies have evolved and changed over the past decade as a series of repeated experiments in claiming, holding, and sharing space on progressively greater scales, affecting those in the present and those yet to come.

My thanks to the Pink Dot organizers for interviews, documents and responses to an earlier draft. For an excellent ethnography of Pink Dot, and the broader context of gay rights in Singapore after independence, see Lynette Chua, “Mobilizing in the Open,” in Mobilising Gay Singapore: Rights and Resistance in an Authoritarian State (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014): 118–45. At the time of writing, Pink Dot has been recently reassessed by a range of scholars, many in linguistics and sexuality studies. See the special issue of the Journal of Language and Sexuality devoted to Pink Dot, particularly Adi Saleem Bharat, Pavan Mano, and Robert Phillips, “Introduction: Pink Dot: Ten Years On,” Journal of Language and Sexuality 10, Issue 2 (July 2021): 97–104; and Pavan Mano, “Disarming as a tactic of resistance in Pink Dot”: 129–56; See also, Alfian Sa’at, Michelle Lazar, Robert Phillips, Pavan Mano, and Adi Saleem Bharat, “CSEAS Lecture Series. The Past, Present, and Future of LGBT Activism in Singapore: A Roundtable on Pink Dot,” University of Michigan, October 25, 2021; and Audrey Yue and Helen Hok-Sze Leung, “Notes towards the Queer Asian City: Singapore and Hong Kong,” Urban Studies 54, no. 3 (February 2017): 754–55.

These include the nation’s national ambassador for tourism, a mythical Merlion comprised of a lion’s head and fishtail, and the friendly visage of Singa the lion who fronted the country’s courtesy campaign.

See, for instance, Pink Dot’s 2011 FAQ, “Pink Dot is the name of the organising group. It references the term, Red Dot, which is often used to describe Singapore. Pink, instead of red, because it is the colour often associated with LGBT (think: pink dollar and pink feather boas) but more importantly, it is the colour of our national identity cards and it is what you get when you mix the colours of our national flag.” Pink Dot, “FAQ: Things to Know About Pink Dot,” Pink Dot SG, 2011, https://pinkdot.sg/2011/05/faq-things-to-know-about-pink-dot/ (accessed 8 December 2021).

See Richard Borsuk and Reginald Chua, “Singapore Strains Relations With Indonesia's President,” Wall Street Journal, August 4, 1998, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB902170180588248000; and Jason Fan, “Former Indonesian president was first to call S'pore a ‘Red Dot’ in 1998,” Mothership, May 4, 2018, https://mothership.sg/2018/05/singapore-little-red-dot/ (accessed February 9, 2022).

Important perspectives on Pink Dot have often addressed its linguistic and discursive aspects in relationship to the city-state and are an integral point of reference. See Michelle M. Lazar, “Linguistic (homo)nationalism, legitimacies, and authenticities in Singapore's Pink Dot discourse,” World Englishes 39, Issue 4 (2020–21): 653–66. Lazar argues that “Pink Dot's linguistics discourse forms a mode of pragmatic resistance in an illiberal nation-state through recourse to a homonationalistic sensibility, which allowed Pink Dot to mobilize the national imaginary to advance the sociopolitical struggles of the LGBTQ community. . . . The presence of linguistic homonationalism by Pink Dot can be said to constitute an aspirational politics. . . . not ‘merely’ assimilationist. As seen through its linguistic and discursive acts of queering Singapore's nationalism, Pink Dot finds ways to ‘speak back’ to power from within the space of discourse itself, rather than through a militant counter-discourse which, given Singapore's current socio-political context, would be politically suicidal.” (p. 664). Thank you also to Gabriella Beckhurst Feijoo for the connection between this spread, and queer theories of traversal upon the grounds of the state e.g., see Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Tendencies (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993).

See the Singapore Criminal Code: https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/PC1871?ProvIds=P4VIII_141- (current version as of December 24, 2021).

Jasbir Puar and Lisa Duggan have produced important U.S.-based queer theories critical of how progressive lesbian, gay, and transgender social movements in the 1990s and 2000s were complicit with neoliberal state policies and economics, national assemblages of Islamophobia, militarism and war, the privatization of gay movements, and focus on gay marriage and nuclear family formations, instead of multi-issue and more radical queer politics. See Lisa Duggan, The Twilight of Equality: Neoliberalism, Cultural Politics, and the Attack on Democracy (Boston: Beacon Press, 2003); and Jasbir K. Puar, Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).

Scholars have contested framing the Pink Dot movement without modified and situated views of the different Singaporean contexts of the Pink Dot’s formation, which are distinct from the U.S. contexts in which Duggan and Puar’s accounts of homonormativity and homonationalism were formed. Audrey Yue and Helen Leung have also noted argued that when analyzing countries like Singapore, “Rather than following the logic of homonationalism, which secures the rights of certain LGBT populations in the name of Western exceptionalism and at the expense of racialised others (Puar, 2007), queer Asian cities such as Hong Kong and Singapore are governed through an illiberal sexuality where an ambivalent logic of liberalism and non- liberalism co-exist concurrently and contradictorily, such as the injection of pink tourist dollars; the diversity of queer commerce; and, the infusion of LGBT pride consciousness into mainstream social justice movements. These practices present opportunities and difficulties that are as much about class as they are about sexual politics and justice.” See Yue and Leung, “Notes towards the Queer Asian City,” 761.

Chua, Mobilising Gay Singapore, 5–6.

Chua, Mobilising Gay Singapore, 4–5. Also see Terence Chong, ed., The Aware Saga: Civil Society and Public Morality in Singapore (Singapore: NUS Press, 2011) for an important account of how an influential NGO for women's rights, AWARE, fielded a takeover of its leadership by conservative Christian organizations.

Chua, Mobilising Gay Singapore, 6.

Sonny Yap, Richard Lim, and Weng Kam Leong, Men in White: The Untold Story of Singapore's Ruling Political Party (Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings, 2009).

Care for attendees had long been a priority of the organizers who created pink slips with instructions and in-case-of-emergency information for participants. They also seek photographic consent before, during and after the event. Photographers are briefed to request permission for photographs focusing on individual attendees, while individuals who do not wish to be photographed are marked and avoided by photographers. After photographs are posted online on social media or websites, or if individuals have a change of heart regarding being publicly shown at the event, organizers will take the images down.

Pink Dot, “FAQ: Things to Know About Pink Dot.”

Organizers notably briefed event security to sensitively respond to and admit attendees whose appearance and photo IDs did not match, including transgender, gender non-conforming attendees, and those participating in drag. Pink Dot SG Facebook post, June 23, 2017.

Alfred Chua, “Security checks, barricades at this year's Pink Dot event,” Today online, May 30, updated May 31, 2017, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/pink-dot-event-will-be-barricaded-security-checks (accessed December 10, 2021).

See Reuters Staff, “Wear White to Protest Singapore Pink Gay Rally, Religious Groups Say,” Reuters via Yahoo News, June 23, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-singapore-protests/wear-white-to-protest-singapore-pink-gay-rally-religious-groups-say-idUSKBN0EY0SB20140623 (accessed 5 December 2021); and Regina Marie Lee, “‘Traditional values’ wear white campaign returning on Pink Dot weekend,” Today, May 23, 2021, updated May 24, 2021, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/network-churches-revives-campaign-wear-white-pink-dot-weekend (accessed December 13, 2021).

For visuals of the barricades and the sign “bridges not barricades,” see Pink Dot SG’s video “Pink Dot 2017: Against all Odds,” July 2, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6eknl1Ko-kw&list=PLMK9qFvgZNro_lBK20QKDGMuCvF2kBVbk (accessed 10 December 2021).

Interview with event organizers conducted in August 2021.

See Pink Dot SG’s “RED + WHITE = PINK (2009 Campaign),” May 6, 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hDdoT7opmrg (accessed December 7, 2021). In this video, allies—friends, family, colleagues—appear as talking heads and speak about their relationships to people who are gay, who by the end of the video, don pink clothing. The segment segues into a grid of screens of pink-clad people and a pink circle. Relatedly, an early promotional video from 2010 focused on multigenerational family relationships with lesbian, transgender, and gay individuals, and how parental and extended family structures were not opposed to––but supportive of––homosocial relationships and transgender identity. See, for instance, ‘Pink Dot 2010: Focusing on Our Families (Part 2),” April 27, 2010: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lI9X89flglA (accessed December 1, 2021).

It bears mentioning that Singapore's Pink Dot gatherings have been taken up as a model for other countries around the world. Between 2011–16, Pink Dot outdoor picnics and gatherings were also held at Penang in Malaysia, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and in North America, in Toronto, Quebec, Utah and Alaska. For a critical analysis of some of these, including the Hong Kong editions, see Benedict J.L. Rowlett and Christian Go, “Tracing trans-regional discursive flows in Pink Dot Hong Kong promotional videos: (Homo)normativities and nationalism, activism and ambivalence,” Journal of Language and Sexuality 10, Issue 2 (July 2021): 157–79.

Ashley Tan, “Singapore Students Holding Non-Confrontational 'Green Dot' Climate Action Rally at Hong Lim Park on September 21, 2019,” Mothership, August 15, 2019, https://mothership.sg/2019/08/green-dot-climate-action-rally-hong-lim/ (accessed February 2, 2022).

See Jurgen Gabel, “Chasing the Pink Dollar,” Bangkok Post, July 25, 2013, https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/361477/chasing-the-pink-dollar (accessed December 8, 2021).

“Government of Singapore warns foreign companies not to support Pink Dot LGBT rally,” Out Leadership, June 8, 2016, https://outleadership.com/insights/government-of-singapore-warns-foreign-companies-not-to-support-pink-dot-lgbt-rally/ (accessed November 30, 2021). Chua observes that “A day after the 4 June event the Ministry of Home Affairs released a statement asserting that ‘foreign entities should not interfere in our domestic issues, especially political or controversial social issues with political overtones. These are political, social or moral choices for Singaporeans to decide for ourselves. LGBT issues are one such example.’ Pink Dot has engendered significant opposition from conservative and Christian groups in Singapore, a country where gay sex remains a criminal offense.” Chua then continues: “activists are aware of how the Singaporean government accused dissident groups of having foreign connections or receiving foreign funds and thus suppressed them for being national security threats. [...] For these interwoven reasons, it is a deliberate tactic of the movement to avoid open affiliations with transnational movements or human rights organizations.” See Chua, “Mobilizing in the Open,” in Mobilising Gay Singapore, 118–45.

Tessa Oh, “Pink Dot Takes Issue with Being Cited by Govt as Example that LGBTQ community does not face discrimination,” Today, May 21, 2021, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/pink-dot-takes-issue-being-cited-govt-example-lgbtq-community-does-not-face-discrimination (accessed December 10, 2021).

Yue and Leung write: “In 2014, community groups considered unpalatable by the organisers––groups organised by sex workers, transgenders and transsexuals––were denied access to the community tent and banned from setting up stalls. Leaflets for circulation also needed to be vetted by the organisers who oversaw the removal of overt political sloganeering (Chan, 2014). Occasional mainstream sexual inclusion, such as through the event, has also come about as a result of the exclusion of queer others.” Yue and Leung, “Notes towards the Queer Asian City,” 755.

George Baylon Radics, “Decolonizing Singapore’s Sex Laws: Tracing Section 377A of Singapore’s Penal Code,” in Columbia Human Rights Law Review, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Fall 2003): 57–99 (97). As Radics observes, “The different treatment of these two sets of plaintiffs reflects how the gay community of Singapore selectively supports the ‘discreet’ and ‘acceptable’ gay couple over the single man who, because of his crime [of having sex in a public bathroom] and willingness to come forward, allowed for the challenge to take place. During Singapore’s recent Pink Dot event, one observer noted, ‘At Pink Dot this year, couple Gary Lim and Kenneth Chee were introduced as its flag-bearers. . . . Yet, as we thanked the brave couple, no one mentioned Tan Eng Hong, who first filed his constitutional challenge to section 377A on 24 September 2010, nor his lawyer M Ravi, who has doggedly championed many human rights cases in Singapore.’ The observer further noted, ‘The problem is, gay men are already unfairly associated with paedophiles, rapists, molesters etc, and constantly have to point out the basic difference. . . . Better then, to hold up the sweetness of Gary and Kenneth’s fifteen-year relationship for everyone to unequivocally cheer and support.” While Tan’s case may be slowly gaining support, Tan has undoubtedly suffered at the hands of the public, his community, and the courts without much support because of the nature of his crime, what it represents, and how society perceives him. Lim and Chee on the other hand are two filial, educated, and ‘discreet’ men in a committed and loving relationship, and therefore have received a tremendous amount of support in their challenge.”

Alfian Sa’at, “Why I Don’t Attend Pink Dot,” rilek corner, July 3, 2017, https://rilek1corner.com/2017/07/03/alfian-saat-why-i-dont-attend-pink-dot/ (accessed 12 January 2022).

Sa’at, “Why I Don’t Attend Pink Dot.”

See Bharat, Mano, and Phillips, “Introduction,” 97–104; and Sa’at, Lazar, Phillips, Mano, and Bharat, “CSEAS Lecture Series.”

The Pink Dot’s 2021 assembly featured videos, pictures, and written posts by organizations such as the T Project emphasizing transgender issues such as housing alongside sex workers’ initiatives such as Project X, Action AIDS, transbefrienders and others whose limited participation or exclusion had been previously critiqued, arguably while expanding the horizon and boundaries of normativity.

See “PINK DOT 2011: SUPPORT THE FREEDOM TO LOVE - 18 JUNE 2011,” May 13, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gxdgx2l0LP4 (accessed 12 December 2021).

Public assembly laws in Section 141-144 of the Penal Code were first introduced in India and then subsequently revised and implemented in Singapore under British colonial rule, criminalizing as potentially unlawful those assemblies of five or more persons. These assemblies are considered unlawful if they overawe by criminal force or show thereof, the government’s legislative, executive branches or the power of public servants; resistance to execution of law or legal process, the commitment of any offenses, criminally forcible forms of possession, the omission of legal entitlements and compel nonlegal activity.

Radics has importantly framed decolonizing 377A as a project of legal decolonization. See Radics, “Decolonizing Singapore's Sex Laws,” 98.

© 2022 8th Triennial of Photography Hamburg 2022 and the author