Kuukuwa O. Manful

On the (Un)formalization of Architectural Design in Ghana

Figure 2. Atakpamé walls, Dompofie, Photo by Dr Ann B. Stahl, 1982. Courtesy University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria, BC, Canada

Figure 2. Atakpamé walls, Dompofie, Photo by Dr Ann B. Stahl, 1982. Courtesy University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria, BC, CanadaMost of the earliest acknowledged Indigenous architects in Ghana were known to have practiced through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in what was then the Gold Coast.1 These architects were mostly men trained in European countries by virtue of their positions as members of elite families in the Gold Coast. Their western education distinguished them from other Indigenous architects and building designers who created architecture long before them and would continue to create long after them. The men known and acknowledged as the first Indigenous Gold Coast architects were not the first to design or build in the country. Still, they were the first to be made legible in the colonial dispensation through the formalization and unformalization of architectural design.

In this essay, I discuss the formalization and professionalization of architecture in the Gold Coast and Ghana and the unformalization of other forms of architecture, using examples drawn from a newly digitized trove of archival architectural images from the late-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century.2 I explore some of the forces which shaped the processes of formalization and regulation of the built environment in colonial Gold Coast, demonstrating that architectural drawings—and the ability to produce them—became a form of professional and formalized currency. I also consider how, because of these processes, the creation of architecture in much of the country was cut off from its communal roots and transformed into the individualized venture we see dominate today.

Contrary to Eurocentric and colonially constituted narratives about architecture in Africa that still prevail to this day, there is a long and ancient history of architecture and architectural knowledge (used here to mean specialized building design and construction) on the continent.3 The dearth—through destruction and decay—of physical and documentary historical sources is a consequence of colonial power that many historians of early African histories must contend with. Yet, by using other sources such as orally transmitted (hi)stories, oral histories, and mythologies, we can address some of the gaps in this knowledge.4

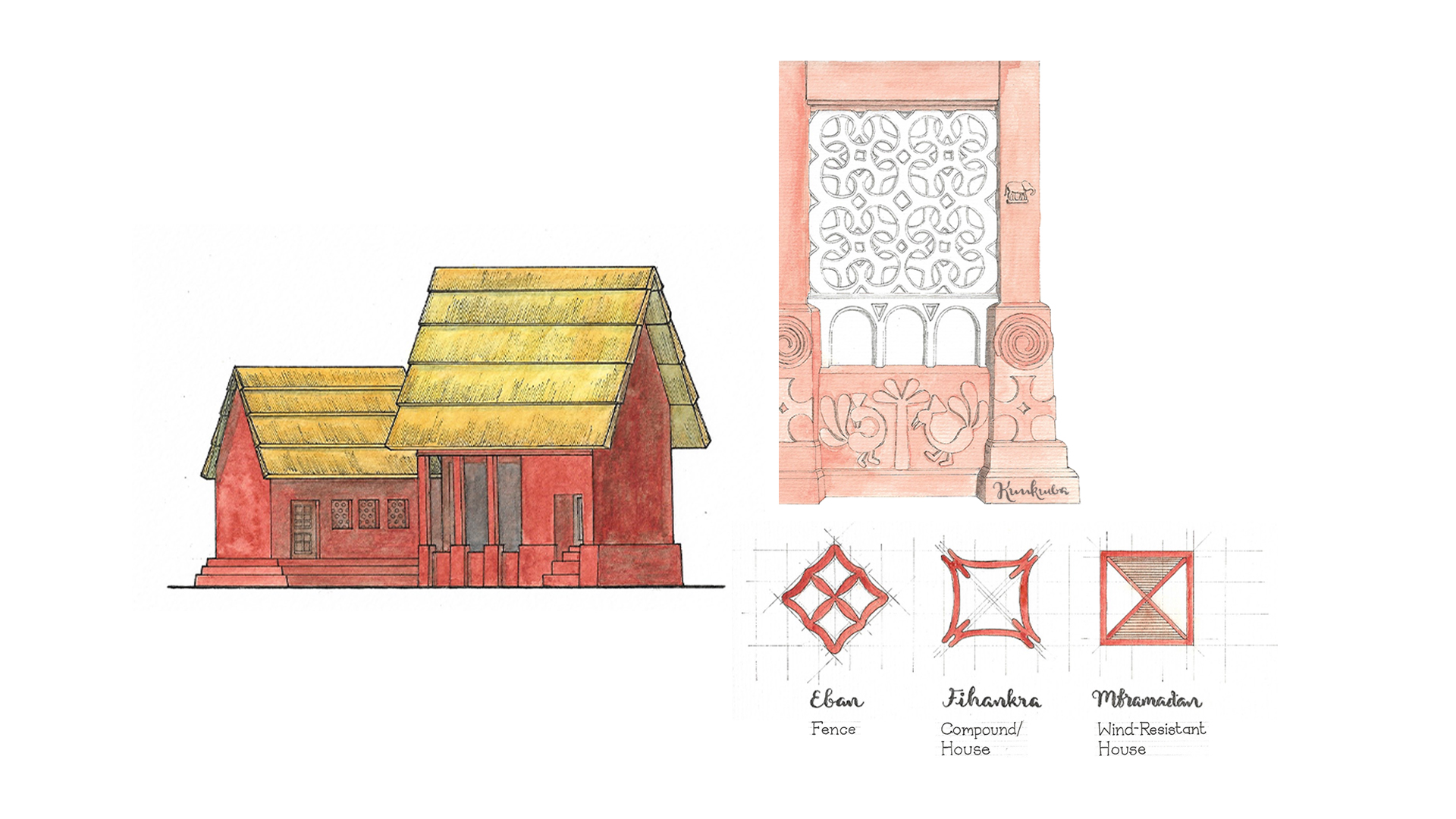

The (hi)stories of the Adansi people point to a long and entwined tradition of architectural knowledge and activity.5 The word Adansi means both the act of building and the foundation of a building, while also naming one of the nine clans of the Asante of present-day Ghana. One of the most widely transmitted ancient creation stories of humankind from Asante mythology reads as follows:

A long, long, time ago, from deep within the Asumegya Forest in Asantemanso, the first people came out of a hole in the ground. These were the forebears of nine clans. To each of them, Ɔdomankoma gave unique gifts and talents. He taught the art of building to the Adansi, and they built the first-ever mud houses when the world was created.6

In Asante (hi)stories attributed to the seventeenth century, the Adansi were regarded for their unique and beautiful architecture, particularly the buildings in their Adanse towns (figure 1). Through this, they inspired and influenced architecture throughout the Asante Kingdom. An extract from the “Adansi Legend of Creation” reads: “Asare Nyansa, the king of the wise, beautified the town of this great empire with many beautiful buildings, and his palace was a stone building.”7

These (hi)stories of Adansi as original, famous, and accomplished builders appear in various sources such as in other clan accounts and dirges, demonstrating the rich, ancient, and socially transmitted evidence of a specialist group of architects.8

Another set of (hi)storical accounts of specialist architect groups can be found when studying the building style known as Atakpamé. The most common use and understanding of the word “Atakpamé” in present-day Ghana is the name given to a type of construction method that is widespread in the southern half of Ghana. An Atakpamé wall (figure 2), which has a finished thickness of about 300mm, is constructed by layering balls of wet, molded earth in a rectilinear frame marked out with pegs and strings.9 Atakpamé is also the name of a town in the northern part of present-day Togo which has existed for centuries.10 It is thought that the Atakpamé building method is named after a group of traveling builders who originated from the town and spread the knowledge of the construction method through the region by word of mouth. The origin mythologies of the Adansi clan and the widespread existence of the Atakpamé building style provides significant evidence of Indigenous architectural knowledge in the region.

As illustrated by both Adansi and Atakpamé architecture and building methods, a key element from these (hi)stories is the communal approach to architecture and building design knowledge in times past. Rather than individually named and known designers and architects, buildings were designed and constructed by clans, communities, and towns known for their specialized expertise and technologies. Design authorship was shared, and the process of building from design and construction was communal until European conquest and colonization disrupted these methods along with many other architectural norms and construction technologies.

The imposition of architectural edifices such as castles and forts and the control of architecture and space were among the many tools and techniques of European colonial domination. Architectural and spatial rule in colonized regions was often enforced by creating town councils and introducing laws and regulations to govern activities in settlements. In colonial Gold Coast, the British government set up town councils chiefly for the purpose of collecting taxes, assessing property values, and drawing up voters’ lists, as well as to “execute the provisions” of various ordinances including The Towns Ordinance created in 1892.11 Under this ordinance, all “streets . . . house(s), building(s), wall(s) or fence(s) upon or adjoining any street” came “under the immediate supervision of the Director of Works,” and it became unlawful for any such constructions to be “erect(ed) . . . without the permission of the Governor.” Offenders could be fined or directed to demolish the construction. The ordinance also applied to existing buildings, walls, steps, verandas and the like which were deemed by the Director of Works to be “an obstruction to the safe and convenient passage along any street.”12

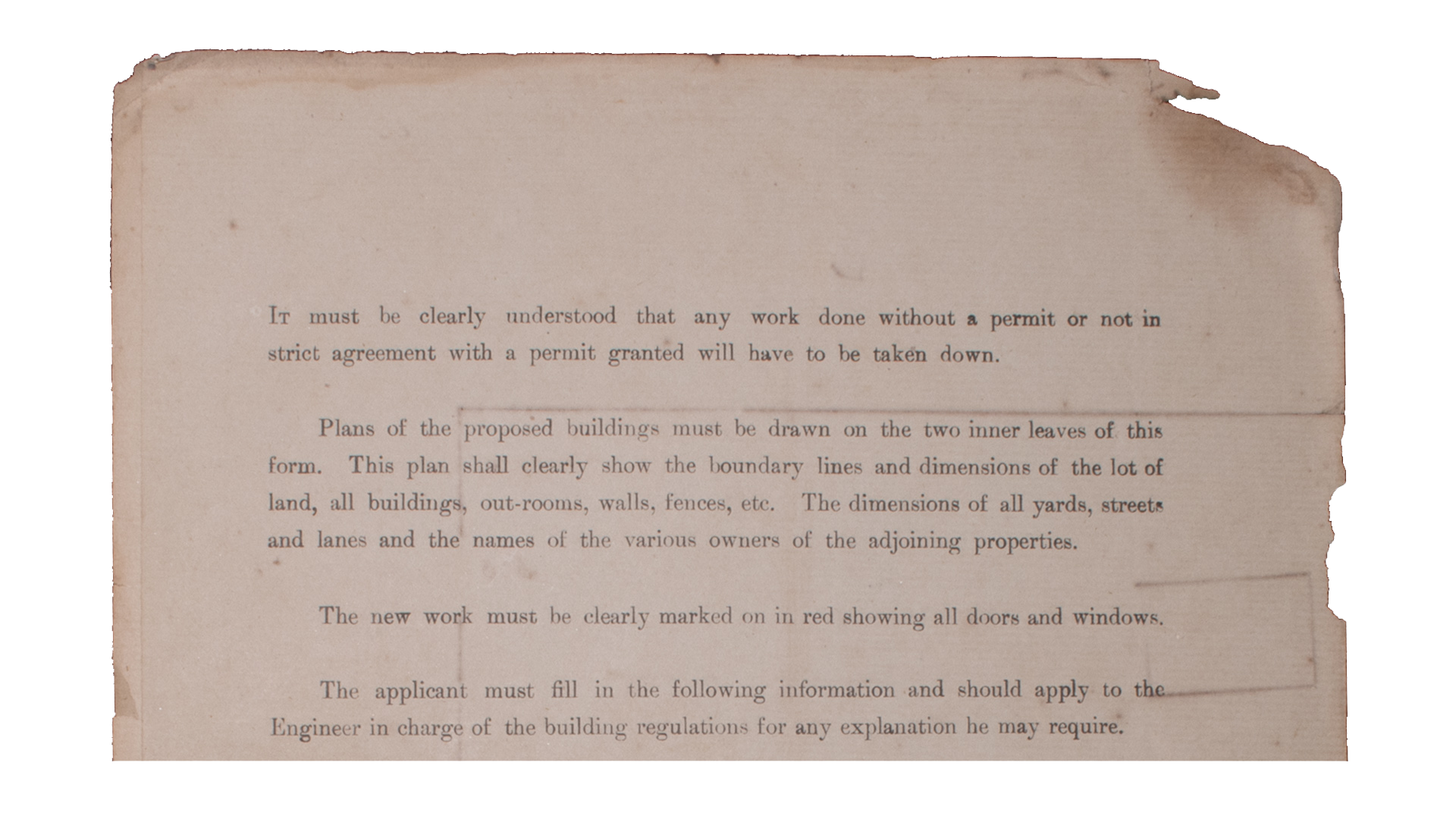

In the capital, the Accra Town Council required that a building permit be obtained before any inhabitant could construct or amend a building on their property.13 As a required component of architectural drawings as part of building permits applications, it was requested that these plans “clearly show . . . all buildings, out-rooms, walls, fences . . . (and) all doors and windows” of the proposed new constructions or alterations (figure 3).14 Permits were sometimes granted or refused based on the materials that applicants intended to build with. For instance, building materials considered more appropriate, such as burnt brick and concrete, were prescribed in place of the more contextually sustainable and affordable “swish” that was commonly used by the inhabitants of Accra.15

This new requirement within building permit applications meant that people who had been engaged in architectural work would have either had to rapidly learn new architectural drawing skills or risk being sidelined. Although it is not known whether Indigenous building construction processes included some form of architectural drawings, the submission of paper drawings to some sort of central authority is considered unlikely. Effectively, by introducing new laws and requirements for paper architectural drawings, the colonial government began a process that diminished the role of Indigenous architectural practitioners who were untrained in the standards of the Western form of the profession.

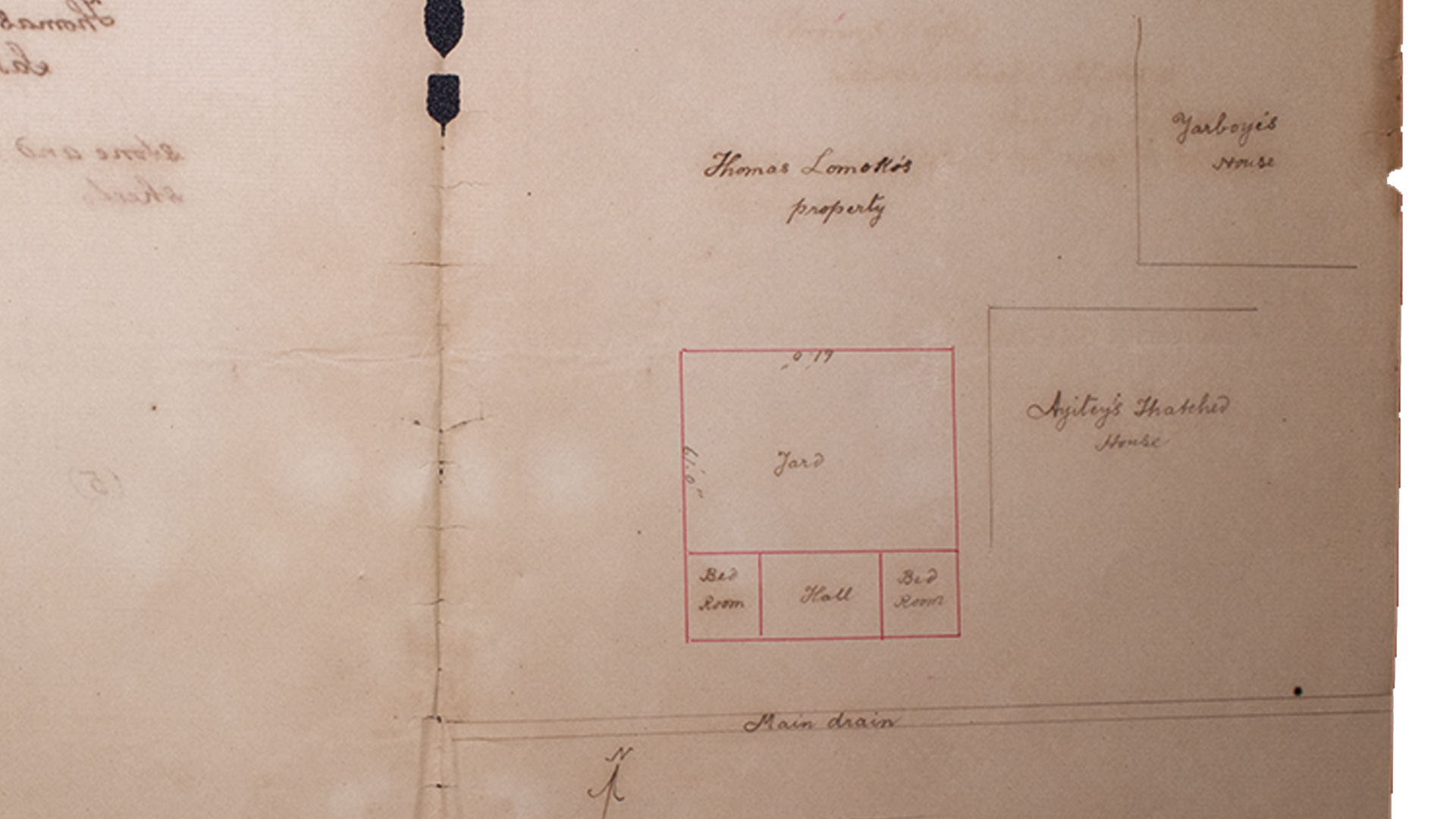

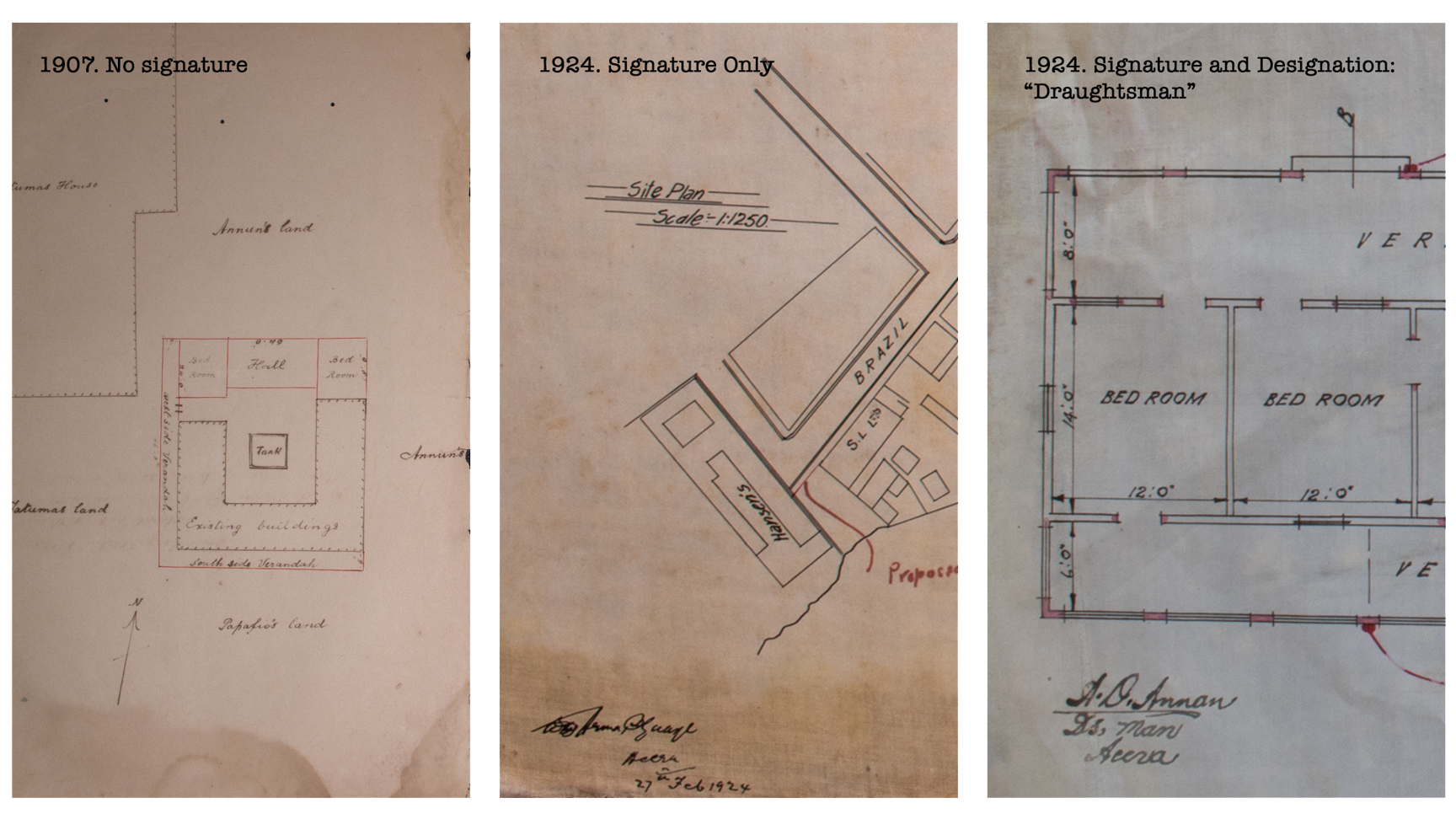

Examining the architectural drawings included in building permit applications submitted to the Accra Town Council from the early 1900s through to the 1940s demonstrates an increasing complexity in the form of the architectural drawings. The trajectory of architectural drawing complexity corresponds with the trajectory of the complexity of building regulations developed by the Accra Town Council, contributing to the professionalization of architecture in the colony.

This trajectory of professionalization is also evident in the archival records; the oldest drawings (1900–the 1910s) are unsigned and show no claim to authorship or specialized professional credentials. However, as a result of these pressures, many drawings from the 1920s to the 1940s began to bear signatures and professional qualifications and credentials including personal stamps. The first architectural drawings from the Accra Town Council Building Permit Application collection digitized by the Accra Archive demonstrate the simple and rudimentary appearance of these documents (figure 4). This would indicate that the person who made it had likely not received formal architectural or draughting training. The drawing is also unsigned, continuing earlier architectural traditions of having no individual authorship.

As time went on, a combination of increased colonial control and consolidation of European influence in the Gold Coast produced higher requirements for complexity and detail for the architectural drawings that accompanied building permit applications submitted to the Accra Town Council. These requirements reflected, reinforced, and influenced the formalization and the professionalization of Gold Coast architecture. As a result, architectural drawings submitted as part of building permit applications began to be signed by individuals, as seen in the image from 1935 below (figure 5). Later on, the signatures begin to include the license number of the draftsmen who made the drawing.

One repercussion of the formalization of architectural methods in the Gold Coast, was that architectural drawings became imbued with material value and importance for the purposes of obtaining building permits—a value that was constituted by the colonial state. In addition to requiring professionals to produce the plans, other recognized professionals were also employed to read, validate, and translate them into built form. These paper drawings circulated within formal spaces of the colony as a currency of the formalized and professionalized building industry, establishing a system of elite training standards as a result. Architectural drawings made by architecture professionals often then had to be procured by clients and exchanged for permission to build granted by the colonial government.

While some forms of architecture in the colonial dispensation were being professionalized and formalized, as evidenced by the increased complexity and marks of individual authorship shown in the images above, other forms were crucially being unformalized, particularly in urban areas. Earth buildings made from unbaked earth bricks can be counted among these unformalized methods where regulations for “one story buildings” required the use of concrete or stone foundations and at least two feet of stone masonry as a base.16 Thatch and palm-frond roofs were also essentially unformalized, as under building regulations, the “approved materials for covering roofs” had to be “non-inflammable,” although special permission could be technically sought to use these kinds of roofs.17 Following this, construction technologies such as Atapkamé fell out of popularity along with the builders who specialized in them, and the communal approaches to architectural production.

For having been treated by governing authorities as undesirable or unlicensed, the Accra Town Council unfortunately has a limited record of unformal architectures. Out in the city, these architectures were considered obsolete, out of place, and often marked for demolition to make way for builds deemed to fit better into colonial visions for the city. These sentiments were reflected in European architectural literature of the time, as the English travel writer Edith A. Browne described when visiting Accra in the 1920s that “mud huts are being removed to afford sites for more . . . commodious business premises with spacious yards.”18

In the colonial dispensation, individual male architects—typically white European, and to a lesser extent Afro-European, African, and Western-trained—assumed increasingly central, essential roles in the (hi)stories of building, forcing Indigenous groups, clans, and communities of builders into historical obscurity. While this diminishing of Indigenous architectural knowledge, practices, and norms was more pronounced in the urban centers and areas with a greater colonial presence, it by-and-large affected the entirety of the occupied Gold Coast territories.

Resistance and contestation are recurrent through historical narratives of colonial control in Africa, and this (hi)story of formalization and unformalization of architecture in the Gold Coast is no exception. Instances of African inhabitants of the colony resisting colonial town planning orders and architectural control by building outside the purview of the state with Indigenous builders, materials, and technologies offer important counterpoints to the strategic formalization of building in Africa. However, the lure of modernity in urban areas aided visions of colonial architectural and urban order. Alongside the more coercive techniques of building regulations, laws, and demolitions, more pernicious influences of class and taste succeeded in the transformation of entire areas such as Accra, where there are currently no remaining examples of Indigenous pre-colonial architecture.

Despite independence from colonial rule, postcolonial African states have largely continued in the same colonial vein of formal and unformal architectural practices with little flexibility in between. Architectural activity is bound by more legislation and architectural drawings have gained an even greater currency. Architectural plans today are more complex than those first received by the Accra Town Council and require greater levels of professionalization to read and interpret. Nevertheless, resistance consistently punctures this narrative. The majority of architecture in Ghana, and Africa by extension, falls into categories of the informal and unformalized, and intentionally so: the criterion of formalized architecture continues to be subverted and challenged by people who willingly design and construct their buildings outside the purview of the state.

Known and acknowledged, as opposed the those that came before that are now unknown and widely unacknowledged; the term architect was a foreign and new concept in the Western sense of it, for reasons I detail throughout this essay. However, I use it here to appropriately situate this historical work.

Unformalisation refers to the diminishing and othering of knowledge, activities, and objects by states and other organizations of authority. This is ongoing research that I have previously explored in my afterword to Architecture and Politics in Africa: Making, living and imagining identities through buildings, edited by Joanne Tomkinson, Daniel Mulugeta, and Julia Gallagher (James Currey, 2022). These are images from the Accra Archive’s ‘building Early Accra’ Project (EAP 1161, available at www.accraarchive.com) which was funded by a grant from the Endangered Archives Programme, supported by Arcadia and administered by the British Library, London, United Kingdom.

Giilstim Nalbantoḡlu, “Toward Postcolonial Openings: Rereading Sir Banister Fletcher's ‘History of Architecture.”’ Assemblage 35 (April 1998) has analyzed Bannister Fletcher’s “canonical . . . comprehensive survey of world architecture” (p.7) and shown how the original tomes, as well as subsequent revisions, have overlooked and diminished non-European architectures. African architectures outside of Egypt do not feature in his original ‘tree of architecture’ at all. Similarly, Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, considered pioneers of architectural Modernism in West Africa, positioned themselves as “invent(ors) (of) town design and building design in West Africa” in a tabula rasa setting where “there was no model for African building” (Jane Drew’s lecture notes, p.4, ca.1988 F&D/4/7, and Maxwell Fry’s memoir, undated, F&D/19/2, RIBA Collections, London, United Kingdom).

I use (hi)stories to denote two aspects of these orally transmitted accounts. They are both histories in the sense that they are communally constituted and accepted chronicles of past events, and stories in the sense that they are narratives constructed to entertain and impart lessons.

See also the Adanse city-state which is one of the Asante states.

Compiled from various orally transmitted accounts.

“History of the Immigrants from Takyiman,” dossier c. 1942, qtd. in Ivor Wilks, “The Forest and the Twis.” Journal des africanistes 75, no. 1 (September 2005): 19–75.

Joseph Hanson Kwabena Nketia, Folk Songs of Ghana (Legon: Oxford University Press, for the University of Ghana, 1963).

Evans K. Essienyi, “Prefabricated Housing, a Solution for Ghana’s Housing Shortage.” Thesis (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2011).

Atakpame is known for a number of other things, such as being the location where the first ever shot fired by a “British” soldier in the First World War was fired. Before that, in 1764, it was where The Battle of Atakpamé was fought between the Asante Empire on one hand and the Akyem Kingdom with reinforcements from the Oyo Empire and the Dahomey Kingdom on the other hand.

“The Towns Councils Ordinance, 1894.” In William Brandford Griffith, Ordinances of The Gold Coast Colony in Force June, 1898 (London: Stevens and Sons, 1898).

Ibid.

The Accra Town Council was formally established in 1898 following the Town Council Ordinance of 1894. For a discussion of earlier attempts to establish the council and the opposition that was put up by African inhabitants, see B. Pachai, “An Outline of the History of Municipal Government at Cape Coast.” Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana 8 (1965): 130–60.

Requirements printed on Accra Town Council building permit application form.

Earthen materials, such as that used in Atakpamé construction. From a building permit granted by Accra Town Council in 1906.

Towns Ordinance 1892.

For approved materials see Towns Ordinance 1892; this permission would be granted by the Governor, through the Director of Works. Thus, it is unlikely that ordinary African residents would have known about or been able to request this special permission as the stipulation was written in English as part of the ordinance.

Browne also wrote about early Christian, Norman, Greek, and Byzantine architecture as part of her popular series Great Buildings, and How to Enjoy Them; Edith A. Browne, Cocoa: Peeps at Industries (London: A. & C. Black, 1920).

© 2022 8th Triennial of Photography Hamburg 2022 and the author