Yechen Zhao

Laying an adequate foundation: currency and photographic authenticity

Figure 4: Warning dialog in Adobe Photoshop

Figure 4: Warning dialog in Adobe PhotoshopAmong the economic measures that constituted President Richard Nixon’s “shock” in 1971 was the suspension of the U.S. dollar’s convertibility to gold, which in effect dissolved the referential connection between currency and commodity. This tight bond between printed paper and precious metal was replaced by the dollar as fiat currency, a kind of money whose value is guaranteed only through regulation and mutual agreement. The material unmooring of the dollar poses a trenchant question about currency’s authenticity that remains difficult to grasp today. In an era when only ten percent of the money in the U.S. economy exists as physical currency, a complex of legal and economic mechanisms establishes a bulwark against what might otherwise be a widespread folk belief in the fraudulence of this money, creating a highly qualified sense of its tangibility or “reality.”1

Because such questions of authenticity and tangibility have long been posed to photography, the occasion of this triennial is an opportunity to touch upon a historically contemporaneous shock in legal doctrine that transformed the rules by which photographs are admitted as evidence in American courts. Coincidentally—but potently—this reshaping of photographic authenticity emerged in response to the prosecution of financial misdeeds, namely check fraud. From here, we can follow the interlocking trajectories of photography and currency both forwards and backwards in time, from the 1869 fraud charges against the “spirit photographer” William H. Mumler to the counterfeit deterrence system that prevents the opening of detailed banknote images in Adobe Photoshop. In so doing, we may examine how authenticity—in both photography and currency—exists in necessary relation to fraudulence.

Formally codified in the years following the suspension of the dollar’s convertibility, this new standard for determining a photograph’s authenticity in American courts was not an end in itself for legal doctrine. Rather, it was the byproduct of a practical solution devised to uphold convictions for check fraud, which were being appealed by defendants on the basis of rules for photographic evidence created nearly one hundred years prior. This older rule places the photograph in the category of “illustrative evidence,” making it a “visual aid” meant to ratify the oral or written testimony of a witness.2 In the 1975 trial United States v. Goslee, Judge Ralph Scalera’s recorded opinion states that the defendant appealed their conviction on the basis of this rule. They objected to the admission of two photographs depicting their fraudulent check-cashing on the grounds that legally admissible photographs “must be identified by someone who observed the scene and events portrayed, and testifies that the photograph accurately depicts that scene.”3 Because the employee who facilitated this process died prior to trial, the photographs were entered as evidence based on the testimony of the store owner and a police officer familiar with the defendant, neither of whom personally witnessed the fraudulent transaction. In brief, the defendant’s appeal against their conviction for fraud rests on the legal authenticity of the photographs that depict their crime. This authenticity was not properly established because the pictures were not introduced with their material referent—the embodied, eyewitness testimony of the cashier who could say, “I was there and this is what I saw.”

Loathe to let a doctrinal archaism get in the way of the state’s power to prosecute financial criminals, Scalera dismissed this argument on the grounds that the doctrine of illustrative evidence is “overly restrictive,” claiming that photography “long ago progressed to the point where courts can rely on its work.” He pointed to an alternative route for establishing a photograph’s authenticity: “under [the silent witness] theory, when an adequate foundation is provided to assure the accuracy of the process producing the photograph, the photograph can be admitted to speak for itself, even though no witness has vouched for its accuracy.”4 The state followed this route in prosecuting the defendant and introduced these photographs through testimony by store owner Thomas A. Joseph, who clarified not only the check-cashing process at his grocery store but also the operation of the Regiscope camera system that captured the defendant’s misdeed (figure 1). Scalera compares this laying of an “adequate foundation” to the actions taken by the prosecution in a similar check forgery case from 1961, where an employee of the firm that installed the Regiscope camera testified to the process by which it worked.5 In codifying a new method for admitting photographs into court, Scalera’s ruling dispensed with the assumption that an evidentiary photograph must somehow refer to the concrete experience of a human witness, because one can instead secure the photograph’s authenticity by favorably portraying the processes that produce it.6

Setting aside the ramifications that followed this revised rule of photographic evidence, note instead how the state arrived in the mid-1970s at a new way of determining authenticity through its attempts to prove fraudulence. More importantly, this transformation of legal doctrine approaches the photograph as an object, bringing attention to the process of making a photograph before scrutinizing its representational content. Though the jurisprudential impact of Scalera’s ruling resonates on a completely different scale than the aptly named “shock” of Nixon’s announcement, a worthy line between photography and currency can nevertheless be drawn because of this close coincidence. In discarding what seemed to be two bedrock referential links—the evidentiary photograph to eyewitness testimony, thirty-five dollars to an ounce of gold—the conceptual priors of monetary policy and legal doctrine enjoyed a brief pas de deux. Without implying any kind of causal relation, we can nevertheless expand the frame to take in a longer history of how the status of the photograph as an object of evidence is mutually constituted by fraudulence and authenticity.

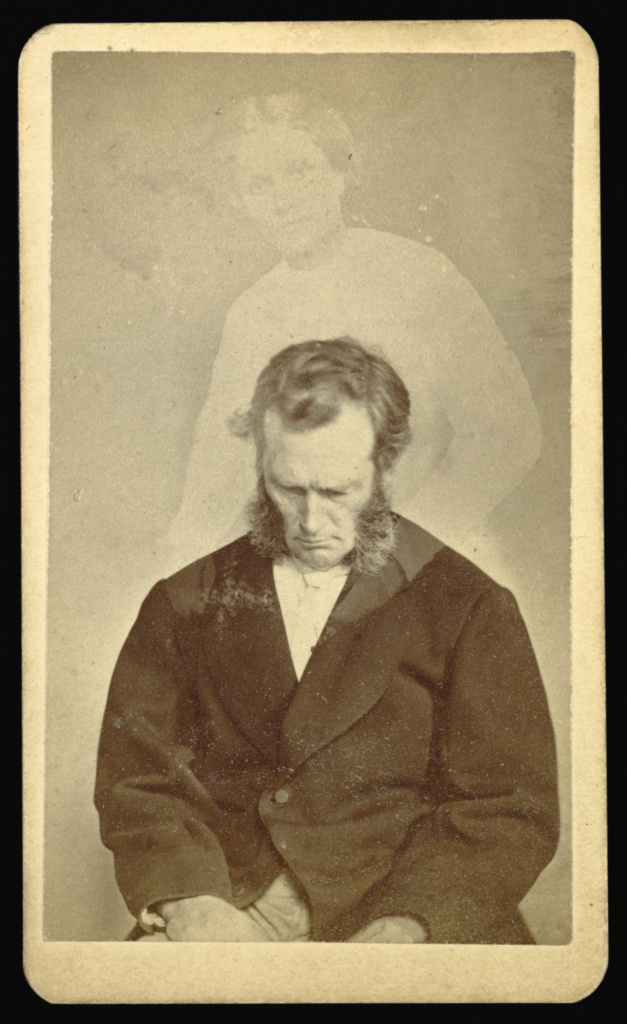

Roughly a century prior, another focal event in this confluence of photography and currency transpired during Reconstruction, and perhaps unsurprisingly, the matter to be discussed is another court case involving fraud. In 1869, the photographer William H. Mumler was charged with fraud for his so-called “spirit” photographs: pictures of living people that included what he claimed to be the hazy likeness of a deceased relative (figure 2). The legal scholar Jennifer Mnookin’s incisive analysis of the case illuminates its underlying subtext in the inherent manipulability of photographs: “was it the defense’s obligation to prove that the photographs were actually produced by spiritual means,” she asks, “or did the prosecution have the burden of proving they were produced mechanically?”7 While the defense called satisfied customers of Mumler’s to demonstrate that his photographs truly convinced people of the existence of spirits, the prosecution called professional photographers to delineate the myriad technical methods of getting pictures with “seemingly ghostly results.”8 As the state would attempt in United States v. Goslee, the prosecution endeavored to use photographs as evidence of fraudulence, and it did so in part by demystifying the processes behind the making of photographs.

Yet even as the prosecution made its case for the fallibility and constructed nature of photographs, the practitioners they called as witnesses “invoked photographic manipulability not to dismantle photographic authority, but to preserve it,” showing how manipulation often left traces on the photographs themselves.9 The analogy Mnookin makes here is worth reading at length, itself a telltale trace of the dialectic between fraudulence and authenticity we are following:

Just as forgery is threatening only when counterfeit currency can be made to look real enough to pass for authentic currency, fake photographs are not alarming unless there is a risk that they might be confused with authentic ones. . . . Not just anyone could perceive the subtle clues that revealed Mumler’s photographs as manipulations; only those who knew how to look properly would see the giveaway signs.10

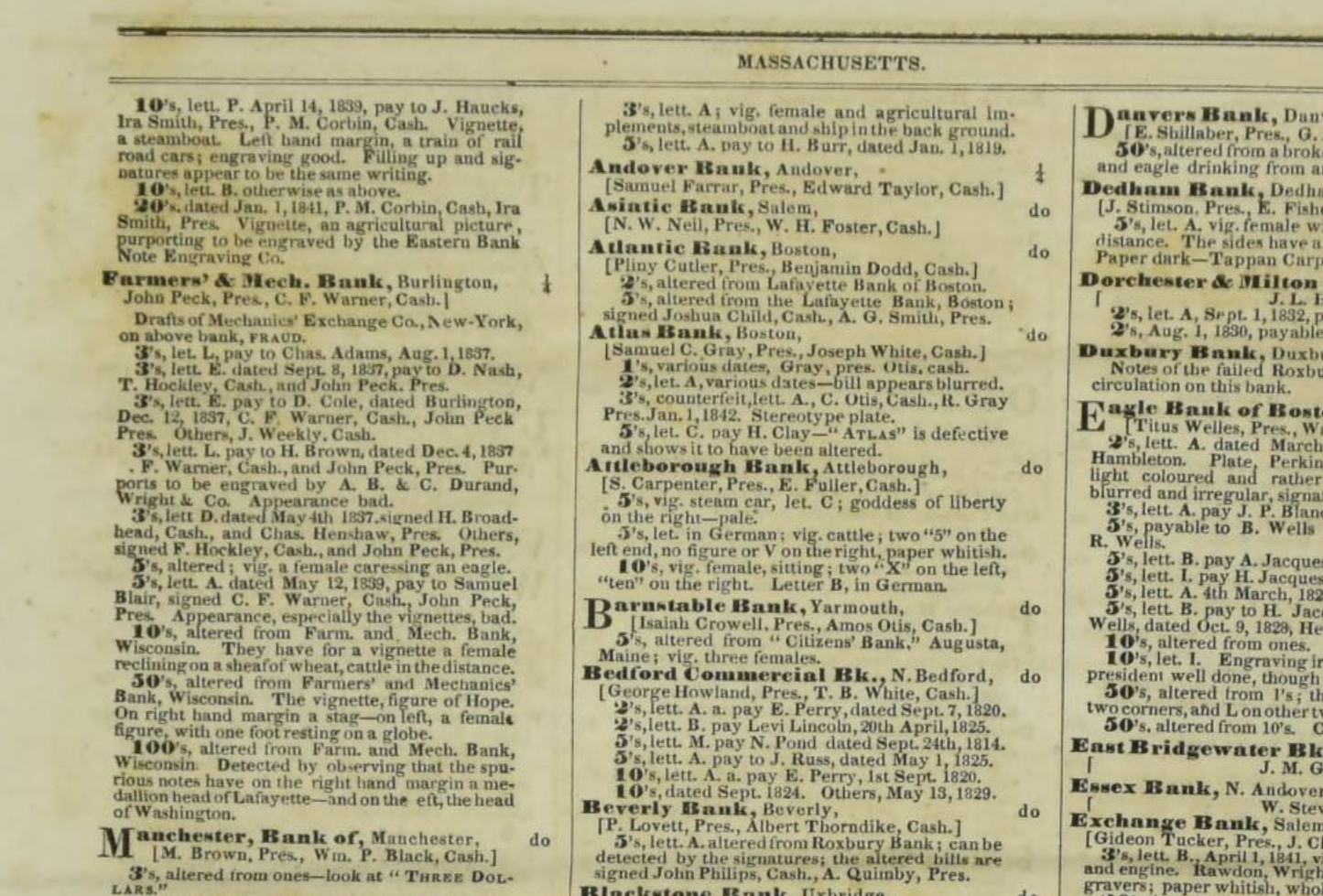

The analogy is not only legally apropos but also sensitive to the historical circumstances of U.S. currency at the time of Mumler’s trial. Having pioneered the use of paper money as its essential currency, the country’s underproduction of domestic coins meant that Americans faced a heavy reliance on foreign coinage as well as a plethora of counterfeit notes; indeed, historians estimate that in the first half of the nineteenth century, between ten to forty percent of paper money in circulation was fake.11 Encountering counterfeit currency was an expected part of life, reflected in the numerous publications of the period that sought to educate consumers on how to detect fake money. Thompson’s Bank Note Reporter (figure 3), the most successful of these periodicals, inventoried through tedious textual description the hundreds of types of bills issued by banks across the U.S. as well as their counterfeit variations, noting minute variabilities in paper quality, ink darkness, and type spacing.12 After all, a business owner’s livelihood depended in part on sensitivity to the materiality of the bills they accepted, an ability to look beyond what a note represented in toto and towards the telltale traces of fraudulence that would render it worthless. The photographers testifying against Mumler staked their professional reputations on this same technique of discernment: authenticity could only be determined through close acquaintance with fraud.

It should be noted that Mumler’s trial took place in the aftermath of another major disruption to U.S. monetary policy, a use of fiat currency far antecedent to the Nixon shock. Between 1861 and 1865, seeking to fund a war against the rebelling southern states and conflate confidence in the nation with confidence in its money, the federal government printed notes exchangeable not for gold but for bonds. More than a historical precedent for severing the referential link between money and metal, this coincidence is worth considering because it established the uniform national currency from which the country’s modern dollar bills are derived. While reincorporating a disaggregated collection of state and local banks under federal charter, the National Bank Act of 1863 sought further uniformity by replacing a myriad array of circulating paper notes with a single currency.

The historian Stephen Mihm helpfully couches this effort between the dialectic of fraudulence and authenticity, explaining how “confidence in the currency . . . now rested on something far more abstract, yet paradoxically more solid: trust in the nation . . . it also meant that counterfeiting, once tolerated or even applauded, now posed a direct challenge to federal sovereignty.”13 Without overstating the connection to the fraud charges brought against Mumler, we can nevertheless ground the analogy to fake money in real historical circumstances. His prosecution speaks to a fear of “counterfeit” photographs taking place against the backdrop of a national campaign against counterfeit currency, initiated by the newly minted Secret Service. Formed in the aftermath of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, this federal agency embarked in 1865 on a nationwide campaign to suppress counterfeiting, quickly discovering that New York City—coincidentally Mumler’s base of operation—had consolidated its position as the central hub for producing fake versions of the nation’s new currency.14 Though the new paper notes produced by the federal government possessed nothing resembling the anti-counterfeiting features on money today, they were far more elaborately designed than the bills previously circulated in local or state economies, prompting a comparable increase in the technological sophistication of the engraved plates used to print fakes.15 In that respect, both the photographers at Mumler’s trial and the counterfeiters pursued by the Secret Service were concerned about the accuracy of the technical processes they wielded, because the authenticity of their work, legal or not, was fundamentally at stake.

Considered in tandem, these two cases illustrate photography and currency’s mutual entanglement with the moving target of authenticity, while demonstrating how that target cannot be struck without first discerning fraudulence. Further, they show how this struggle primarily takes place over material processes, with visuality a secondary concern. In the framed question of authenticity versus fraudulence, the tangible traces reflected by decisions made in the process of printing of a photograph or banknote take precedence over their representational content.

To position this discussion within a visual art context, a good place to land are remarks made by the photographer Neil Selkirk on his experience of printing from Diane Arbus’s negatives for her posthumous retrospective. From the filed-down negative carrier to the developer mix, his technical explanation of the process finds the devil in the details when it touches on the tiny cardboard strips found taped to Arbus’s enlarger. Cut from the cheap boxes holding her negative sleeves, these fragile pieces let Arbus create “on each occasion a unique controlled accident at the edges of her photographs,” constituting the now-famous rough black borders that frame many of her most recognizable pictures.16 Selkirk describes how “trying to precisely replicate that accident was a near-absurd exercise,” but concludes his essay by reaffirming its importance and necessity.17 Even as the highly-specific materials Arbus used have “changed or simply disappeared,” the task “remains the same as it was the day I first entered her darkroom . . . to reinvent the process in order to remain true to the essence: that no one doubts a Diane Arbus photograph.”18 As master printer for the Arbus estate, Selkirk’s darkroom labors involve crafting a process that delivers prints respectful of what he calls her “need to make prints that conveyed the authenticity of the moment without getting in the way of the picture.” For Selkirk, this is only achieved through intimate acquaintance with all the ways of getting it wrong and all the ways in which the “unique quality of Diane’s prints” may be misrepresented.19 Museums, galleries, and collectors might qualify that an Arbus photograph in their possession was printed by Selkirk, but they are unlikely to doubt its authenticity.

By way of closing, it is worth reflecting on how materiality and process remain live issues when interrogating the authenticity of digital constructs. In such analyses, even virtual objects pay respect to material constraints. Hany Farid’s recent handbook Photo Forensics not only explains that the titular practice “emerged to restore some trust to photography” in response to “technology that can distort and manipulate digital media,” but also dedicates a chapter to “physics-based” methods of authenticating digital images, which rely on real-world principles of shadows, lighting, and reflection to uncover telltale traces of manipulation.20 The material remainder is equally a matter of concern for digital reproductions of money. The Counterfeit Detection Act of 1992, for instance, permits color illustrations of U.S. currency provided that “all negatives, plates, positives, digitized storage medium, graphic files, magnetic medium, optical storage devices and any other thing used in the making of the illustration . . . are destroyed and/or deleted or erased after their final use.”21 This restriction, most commonly encountered in the inability to open detailed images of banknotes in photo editing software (figure 4), belongs to a larger counterfeit deterrence system commissioned by a global consortium of central banks.22

Though the elaborate security features on banknotes become less relevant as physical currency becomes an ever-smaller fraction of the financial assets held worldwide, even the decentralized and dematerialized cryptocurrencies of the past two decades are fundamentally concerned with eliminating fraud while guaranteeing authenticity. In its attempt to create rapidly updating and networked global ledgers for transactions, the blockchain system upon which such currencies are based more than superficially resembles the unique serial number on a $100 bill. These currencies rely on mathematical functions called “hashes,” characterized by their ability to take any arbitrary data and transform it into a specific value. New tokens of these currencies are then minted by expending computational power to generate new solutions to these functions. One can think of this “proof of work” as a process of finding authenticity through fraudulence: millions of kilowatt-hours of electricity are expended feeding bogus answers to the hash before the real one is eventually discovered.

The reserve balances of U.S. currency can be found at https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/.

Jennifer L. Mnookin, “The Image of Truth: Photographic Evidence and the Power of Analogy,” Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities 10, Issue 1 (1998): 43–45.

United States v. Goslee, 389 F. Supp 490 (W.D. Pa 1975).

United States v. Goslee, 389 F. Supp 490 (W.D. Pa 1975).

United States v. Goslee, 389 F. Supp 490 (W.D. Pa 1975).

Mnookin, “The Image of Truth,” 73.

Mnookin, “The Image of Truth,” 30.

Mnookin, “The Image of Truth,” 36–37.

Ibid., 37. “Witness after witness described in great detail these different methods, which ranged from relatively simple practices like exposing a single place twice, to complex processes like the use of microscopic lenses.” For more on William Mumler, see Louis Kaplan, The Strange Case of William Mumler, Spirit Photographer (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2008).

Mnookin, “The Image of Truth,” 37.

Stephen Mihm, “Passing and Detecting,” in A Nation of Counterfeiters: Capitalists, Con Men, and the Making of the United States (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2007), 209–59.

Mihm, “Passing and Detecting,” 239–45.

Mihm, “Passing and Detecting,” 340.

Mihm, “Passing and Detecting,” 345–47.

The U.S. Currency Education Program of the Federal Reserve Board maintains information on the security features of all circulating banknotes. See https://www.uscurrency.gov/denominations. The federal government has also alleged that from the 1980s onwards, an extremely high quality, intaglio-printed counterfeit “superdollar” has been in worldwide circulation. See Stephen Mihm, “No Ordinary Counterfeit,” New York Times Magazine, July 23, 2006, which reports on the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s investigations “Royal Charm” and “Smoking Dragon,” which seized a massive quantity of these high-quality counterfeits: https://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/23/magazine/23counterfeit.html.

Neil Selkirk, “In the Darkroom,” in Diane Arbus: Revelations (New York: Random House, 2003), 273 (emphasis added by author).

Selkirk, “In the Darkroom,” 273.

Selkirk, “In the Darkroom,” 275.

Selkirk, “In the Darkroom,” 275.

Hany Farid, “Introduction,” in Photo Forensics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 1.

18 U.S.C. § 504(1), 31 CFR § 411.1.

Adobe’s policy can be found at https://helpx.adobe.com/photoshop/cds.html. For the global rules, see https://rulesforuse.org/.

© 2022 8th Triennial of Photography Hamburg 2022 and the author