Michelle Williams Gamaker

Thieves (or Searching for Sabu and Anna May)

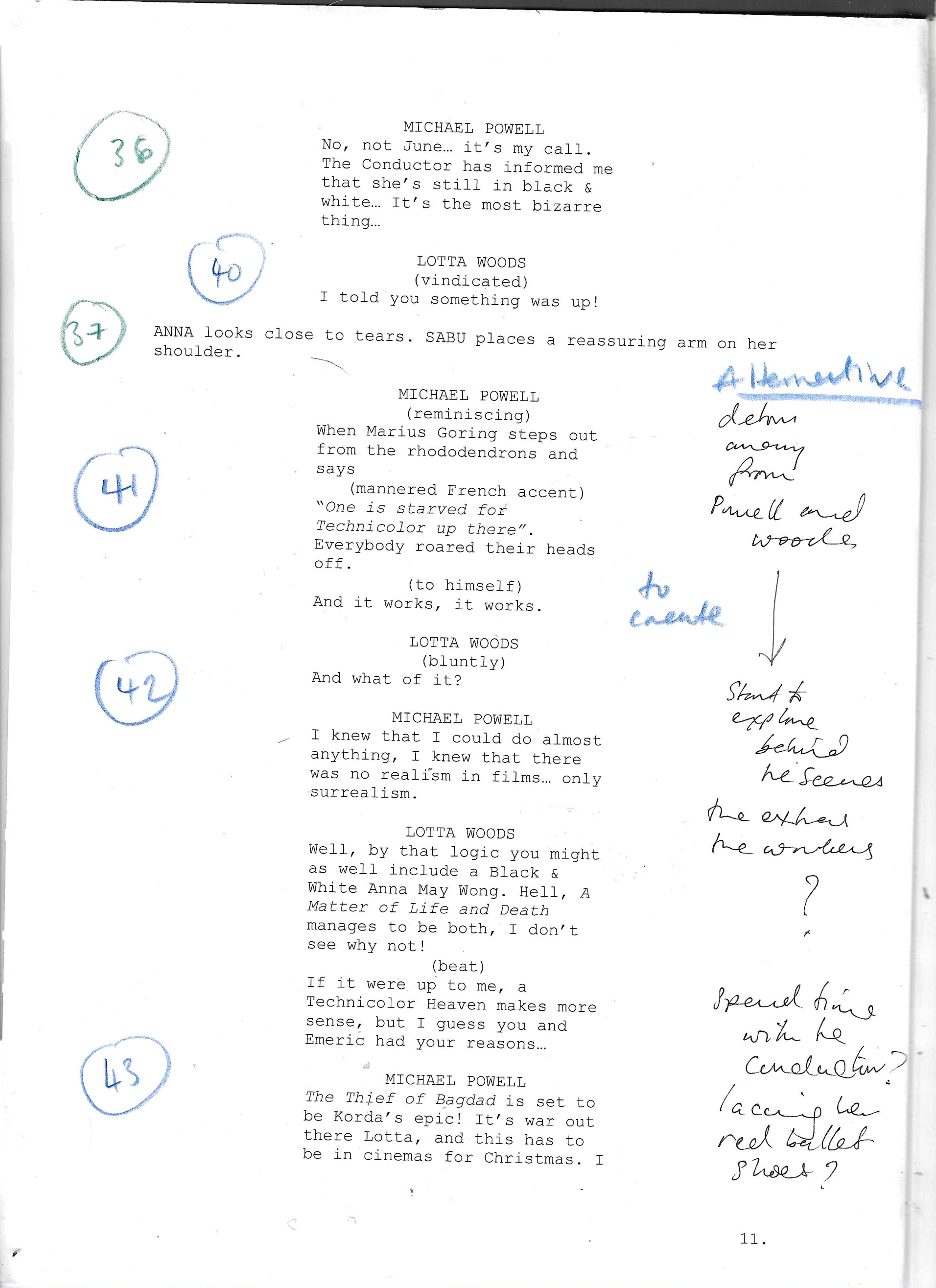

Sabu, 2022. Courtesy the artist © Michelle Williams Gamaker

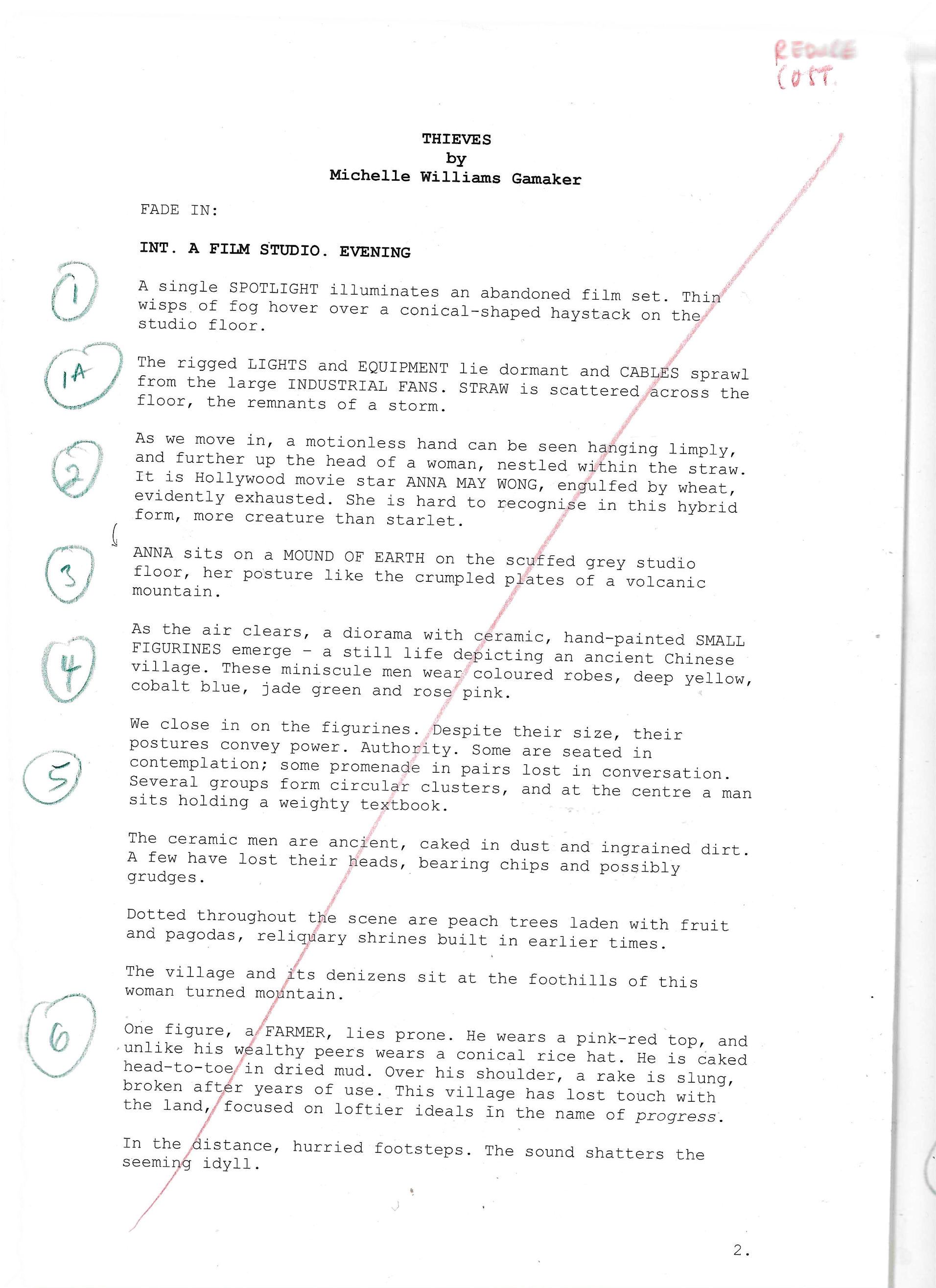

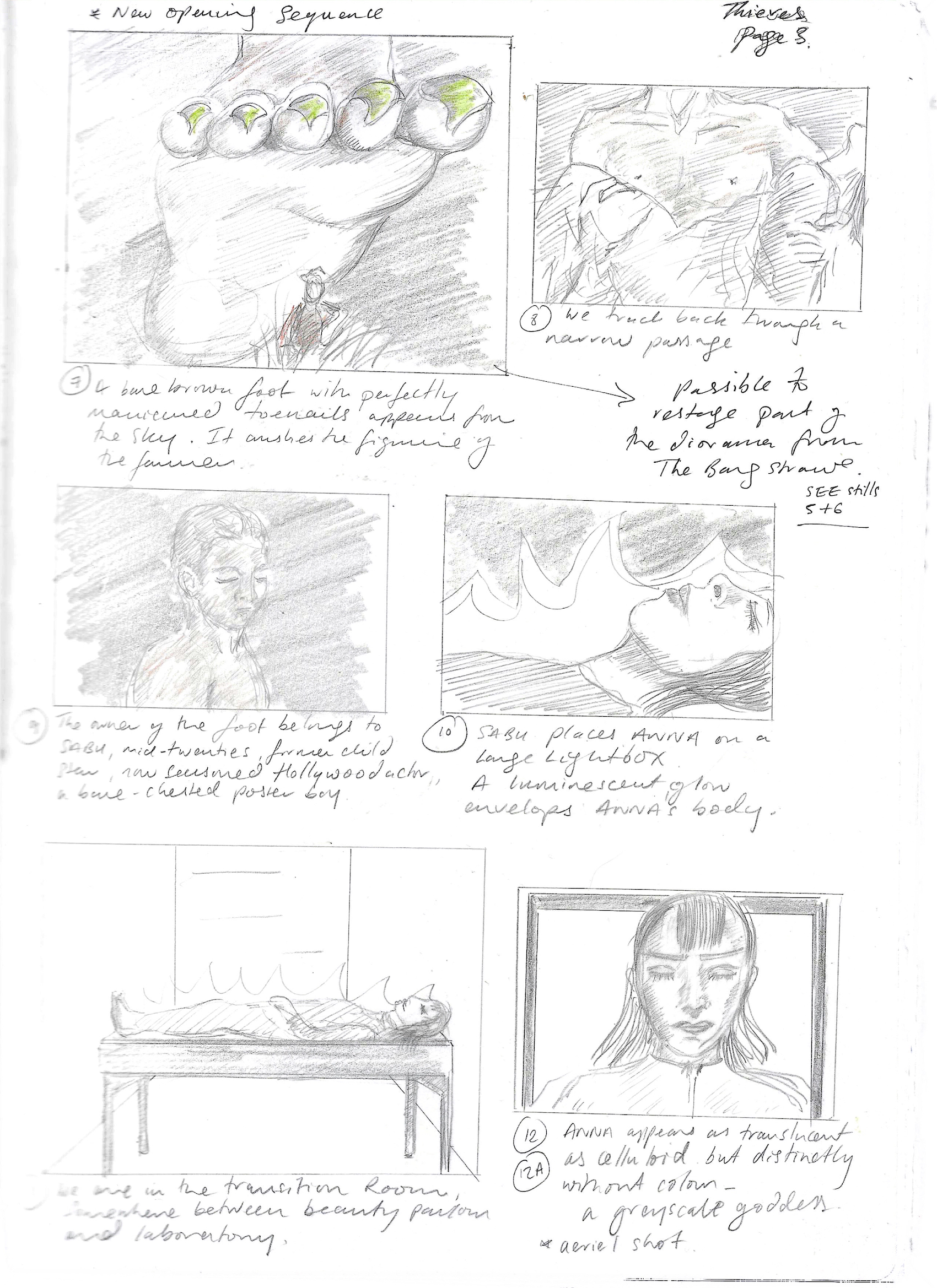

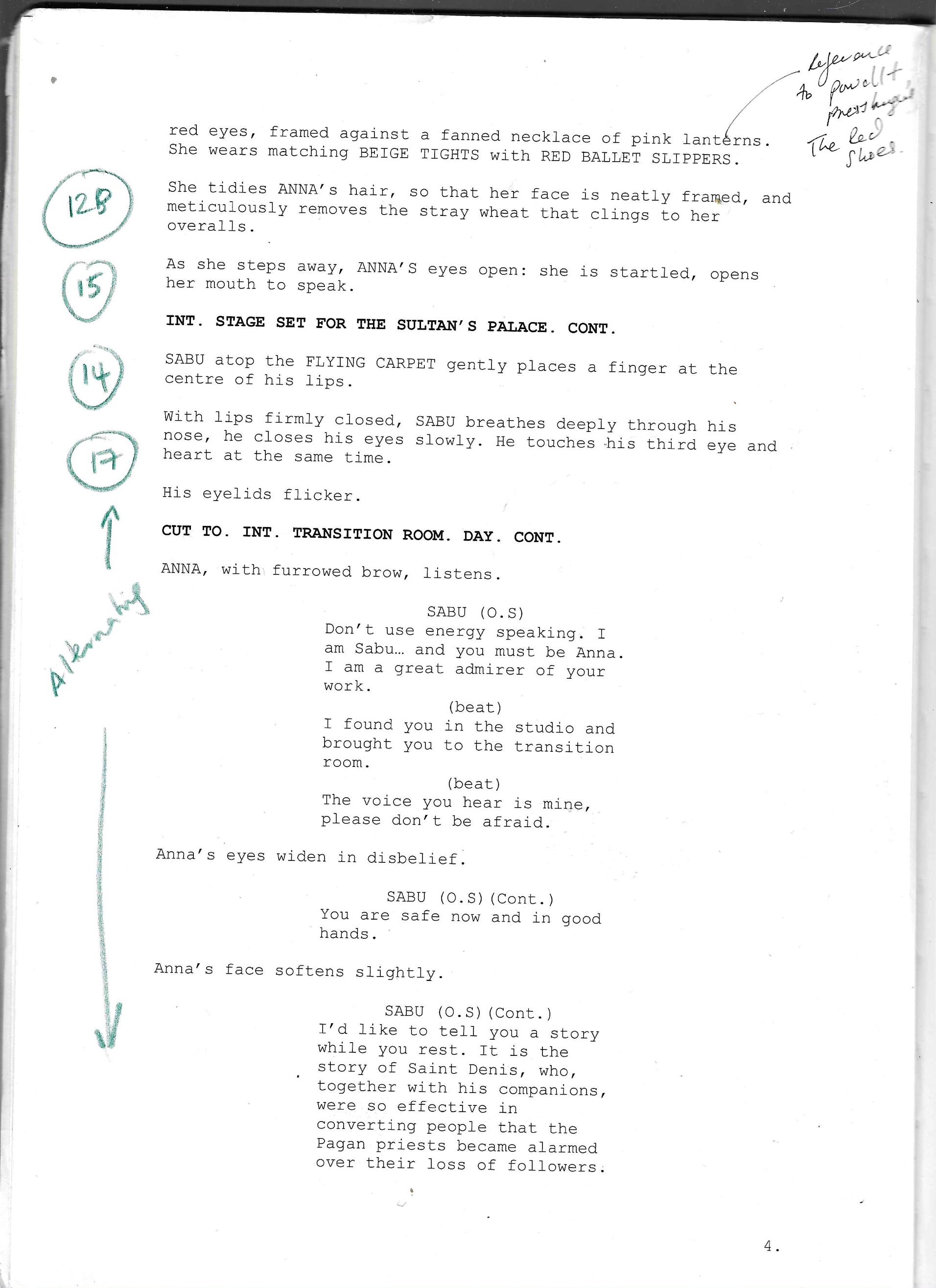

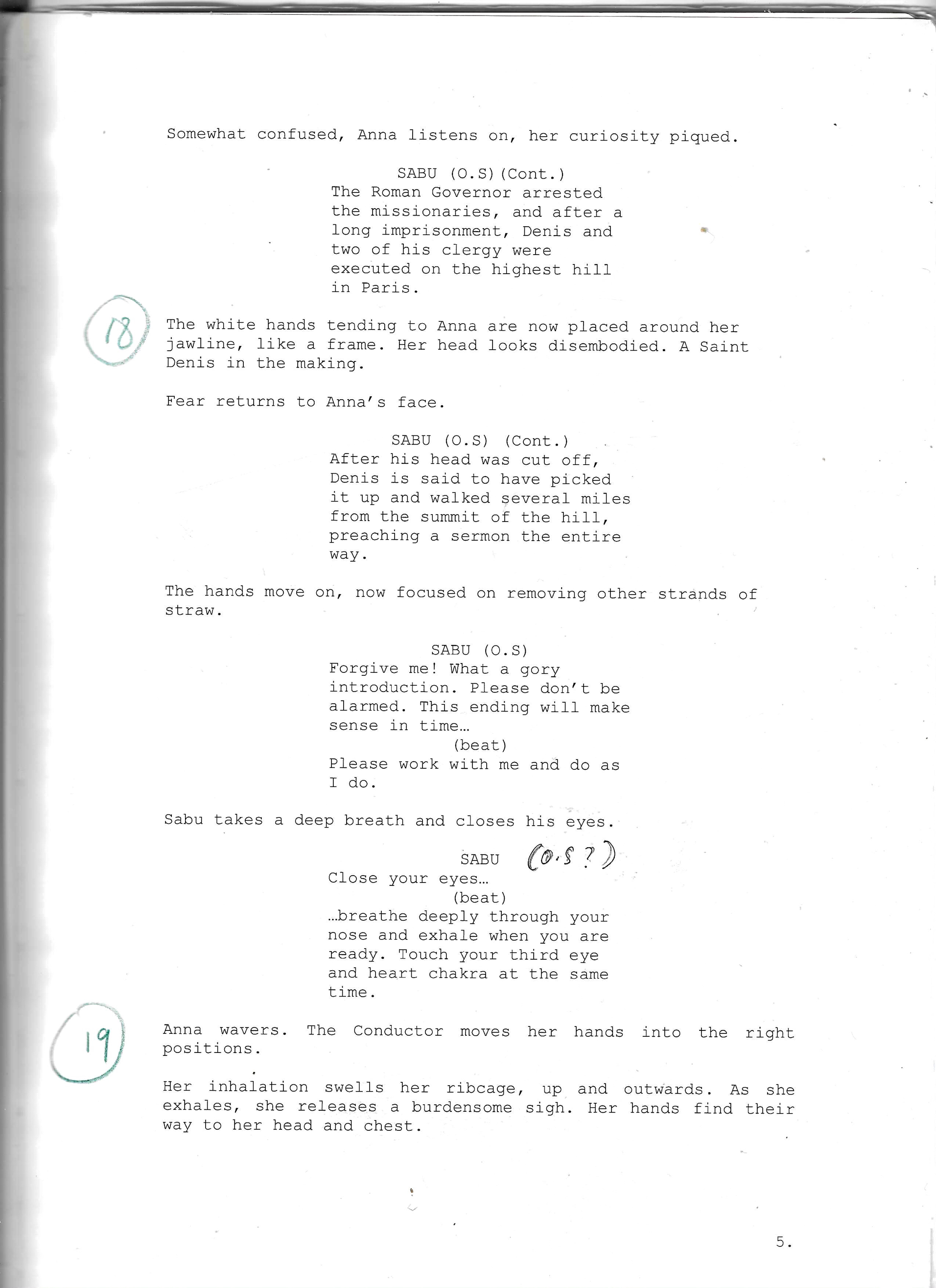

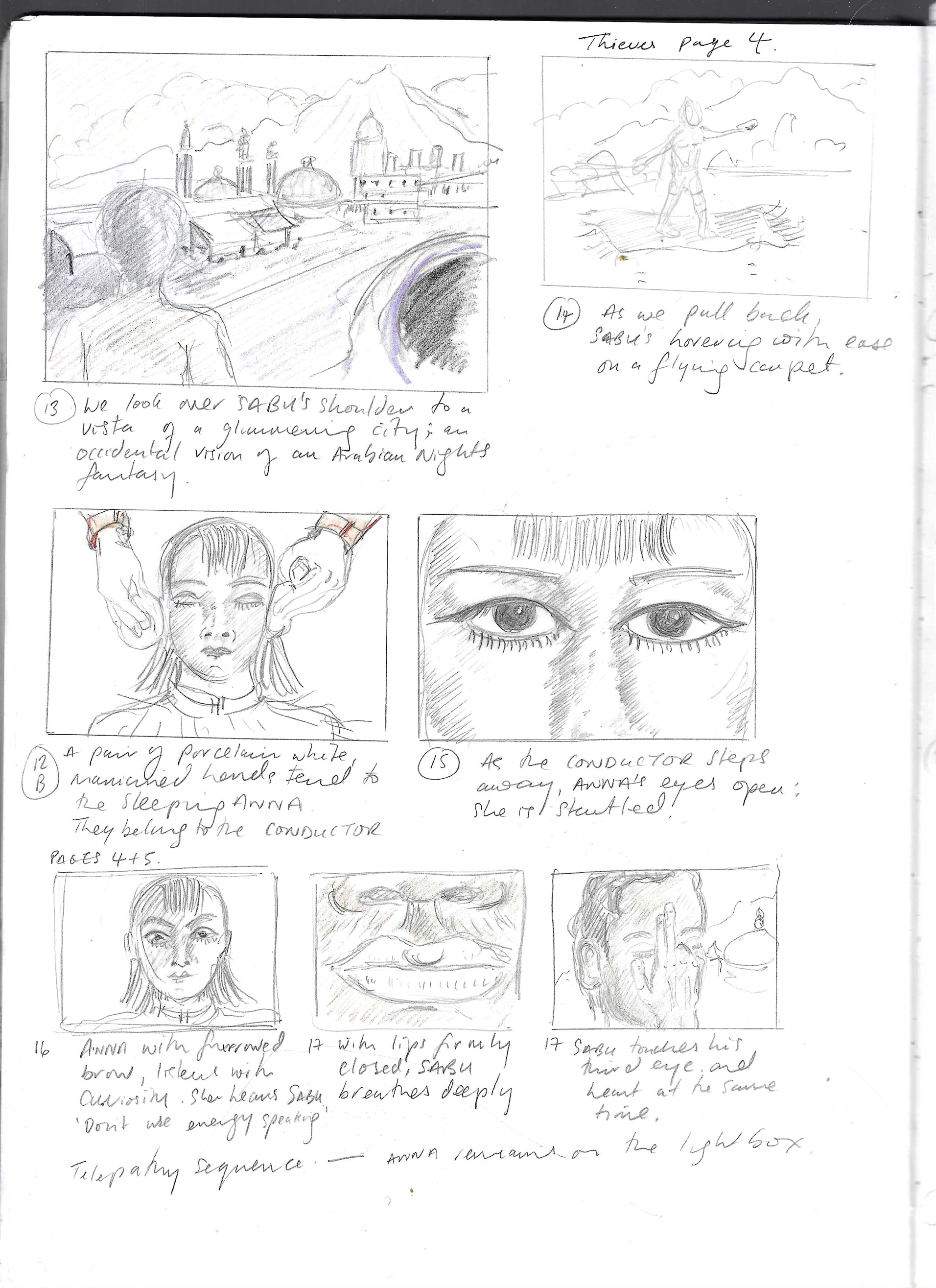

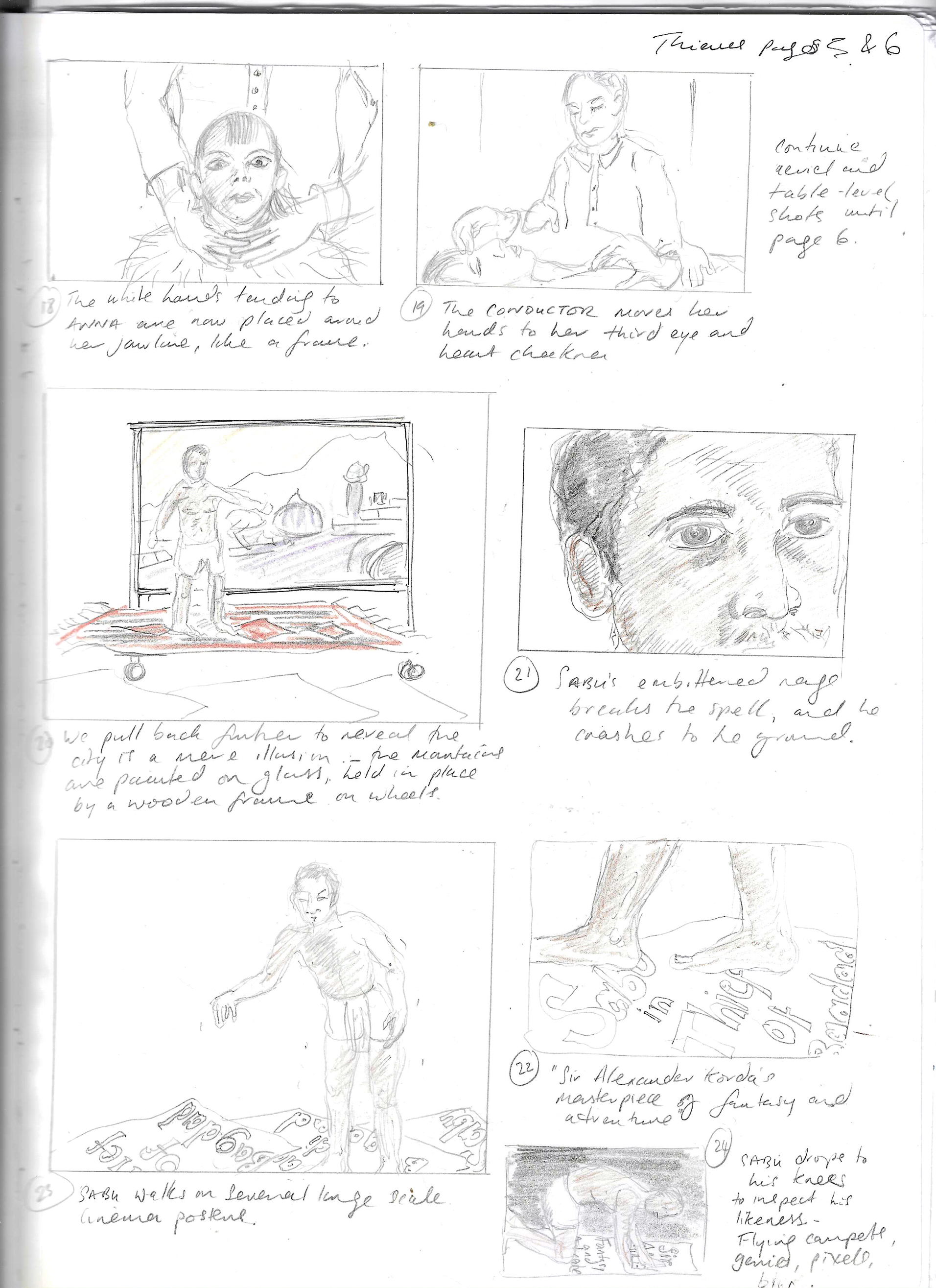

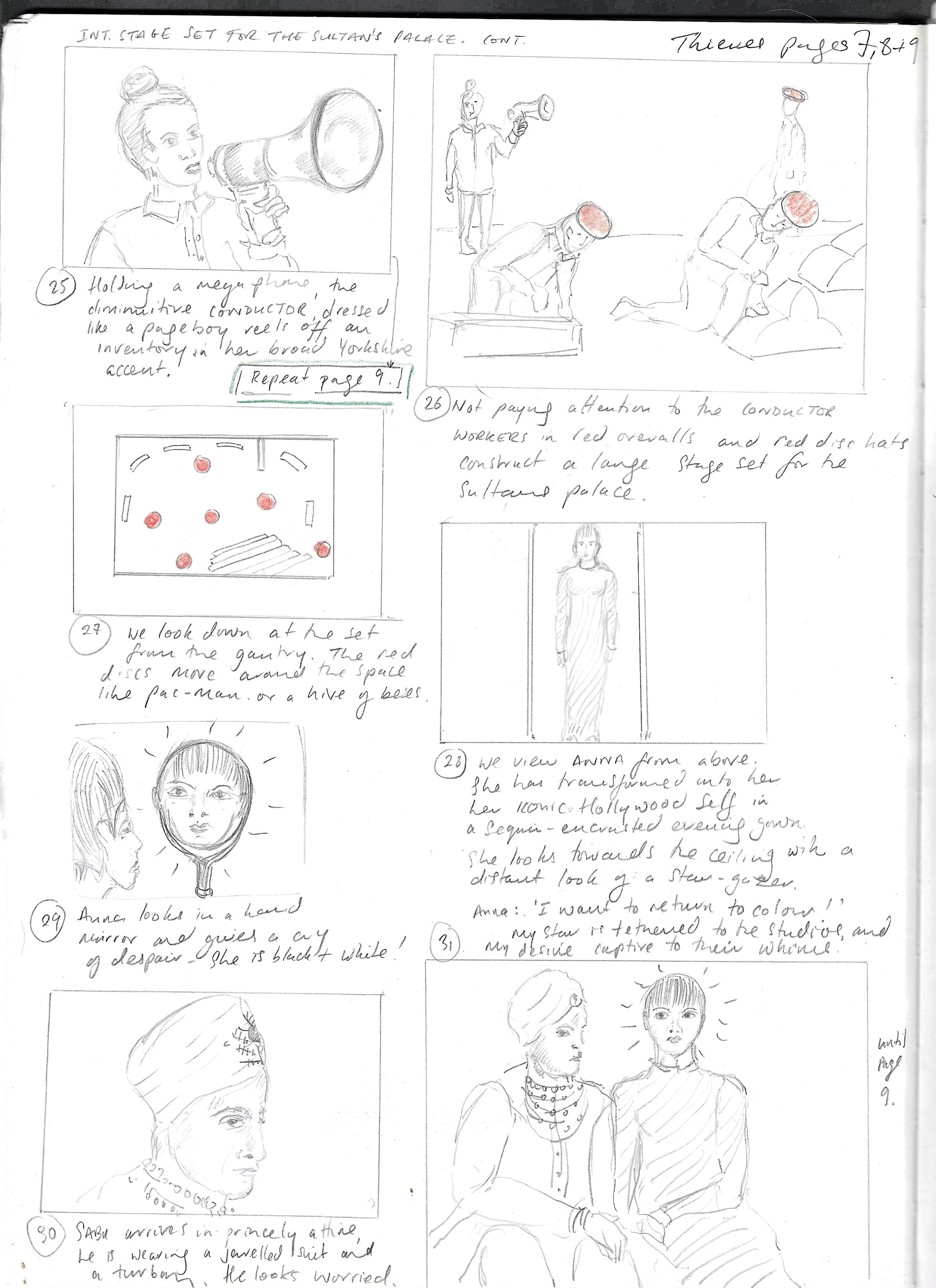

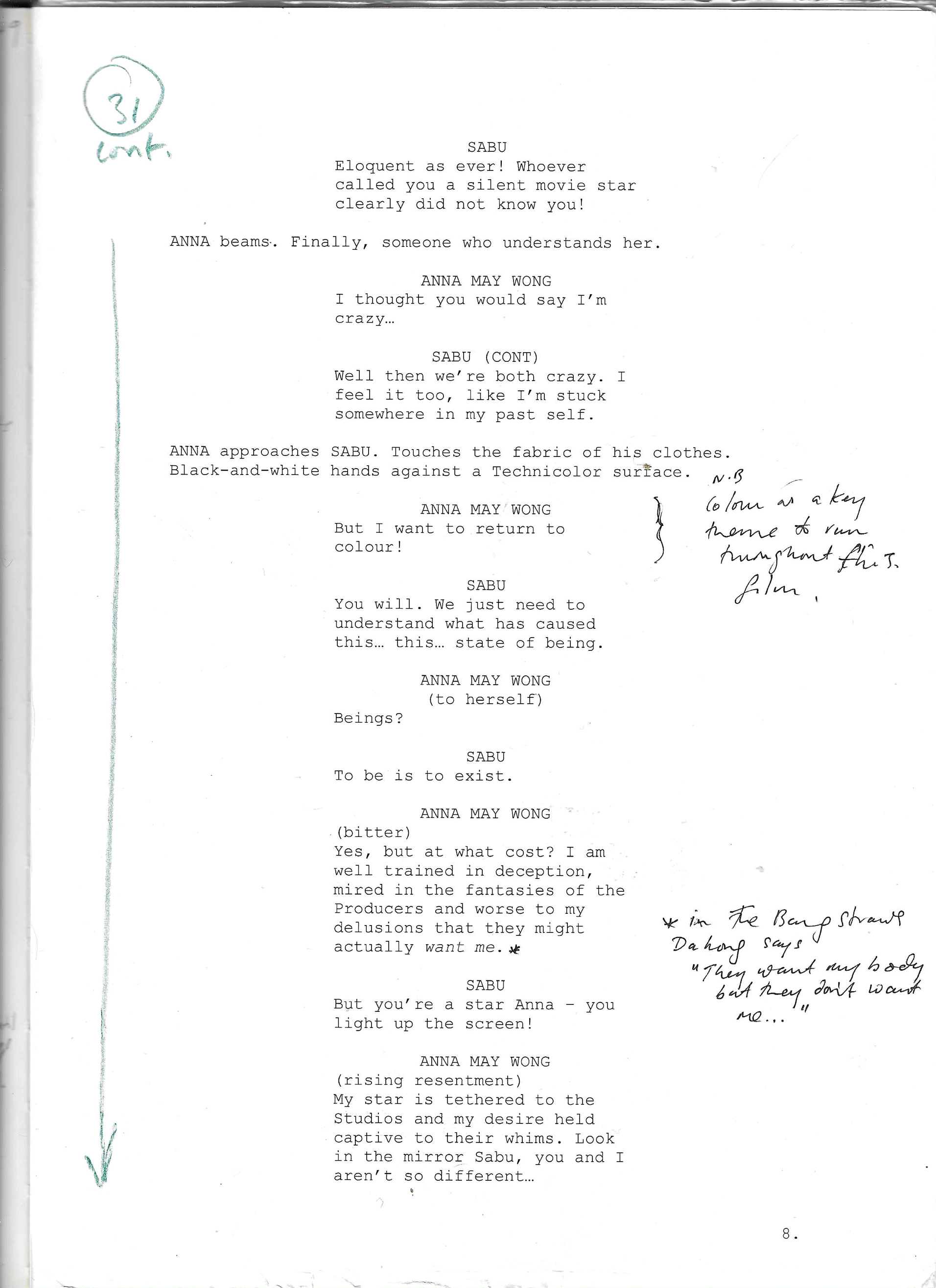

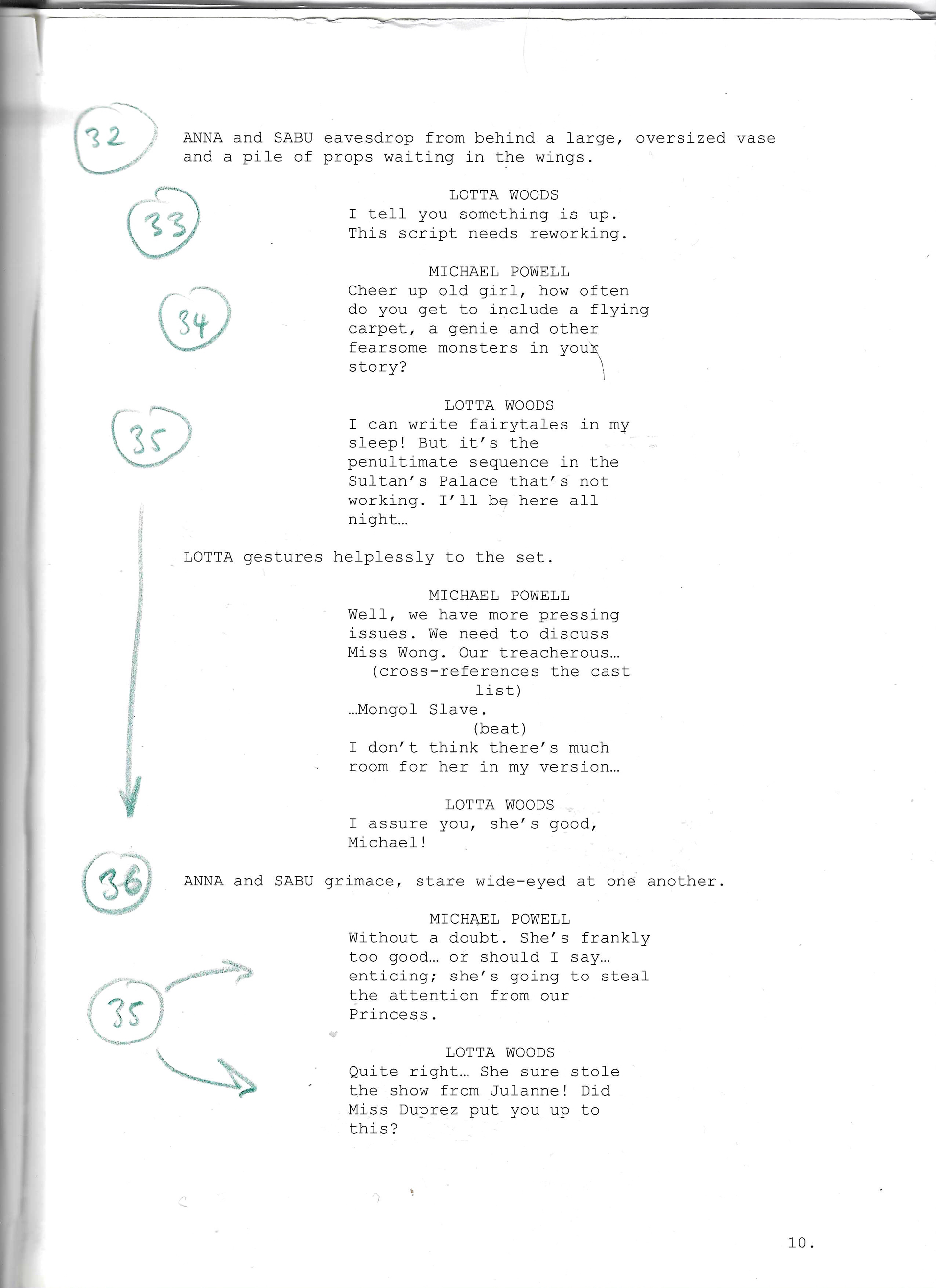

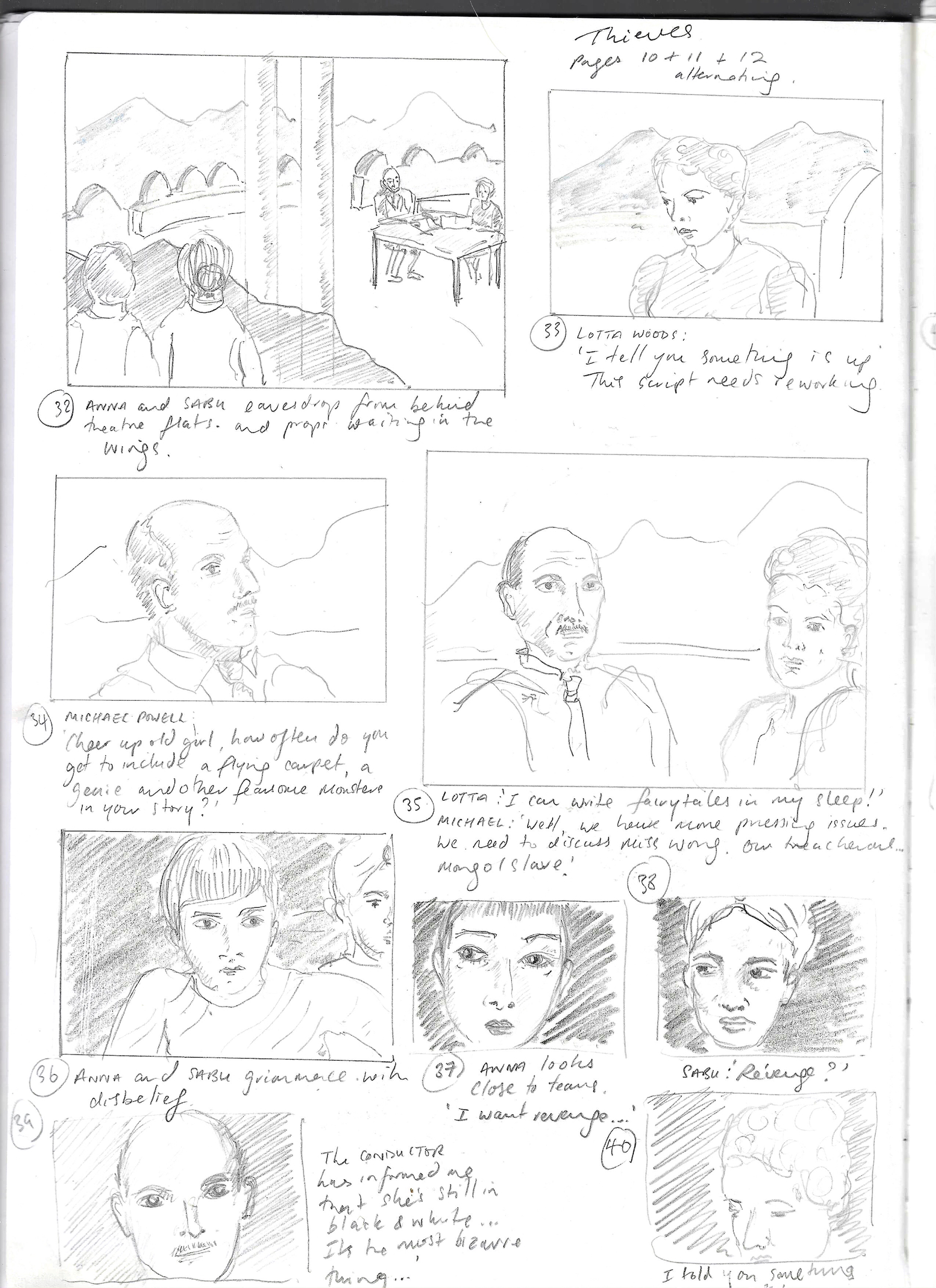

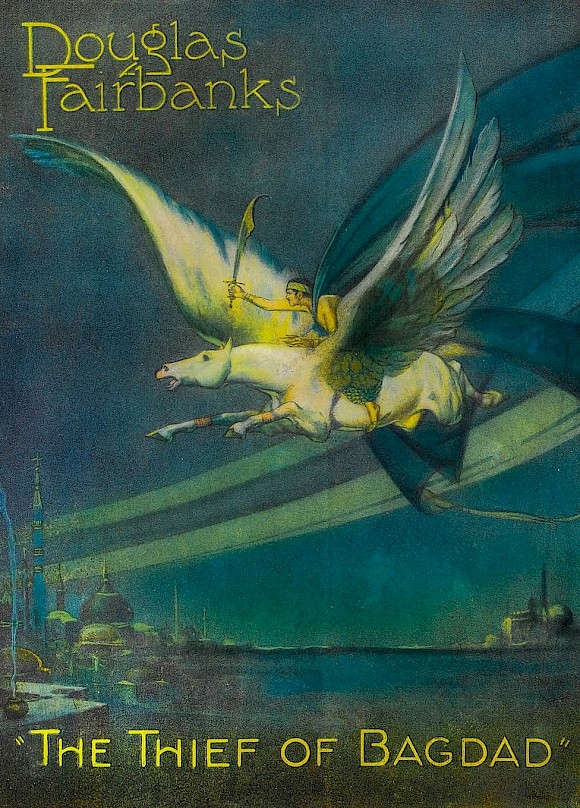

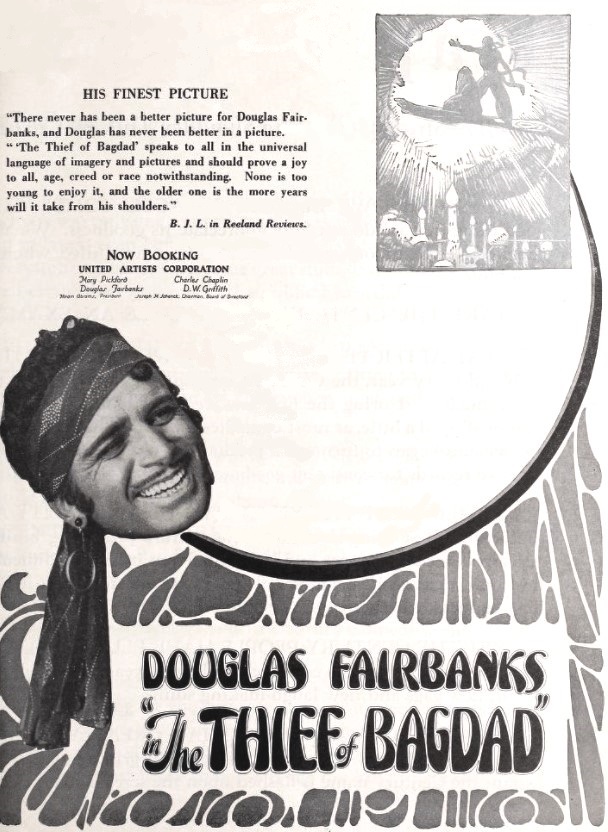

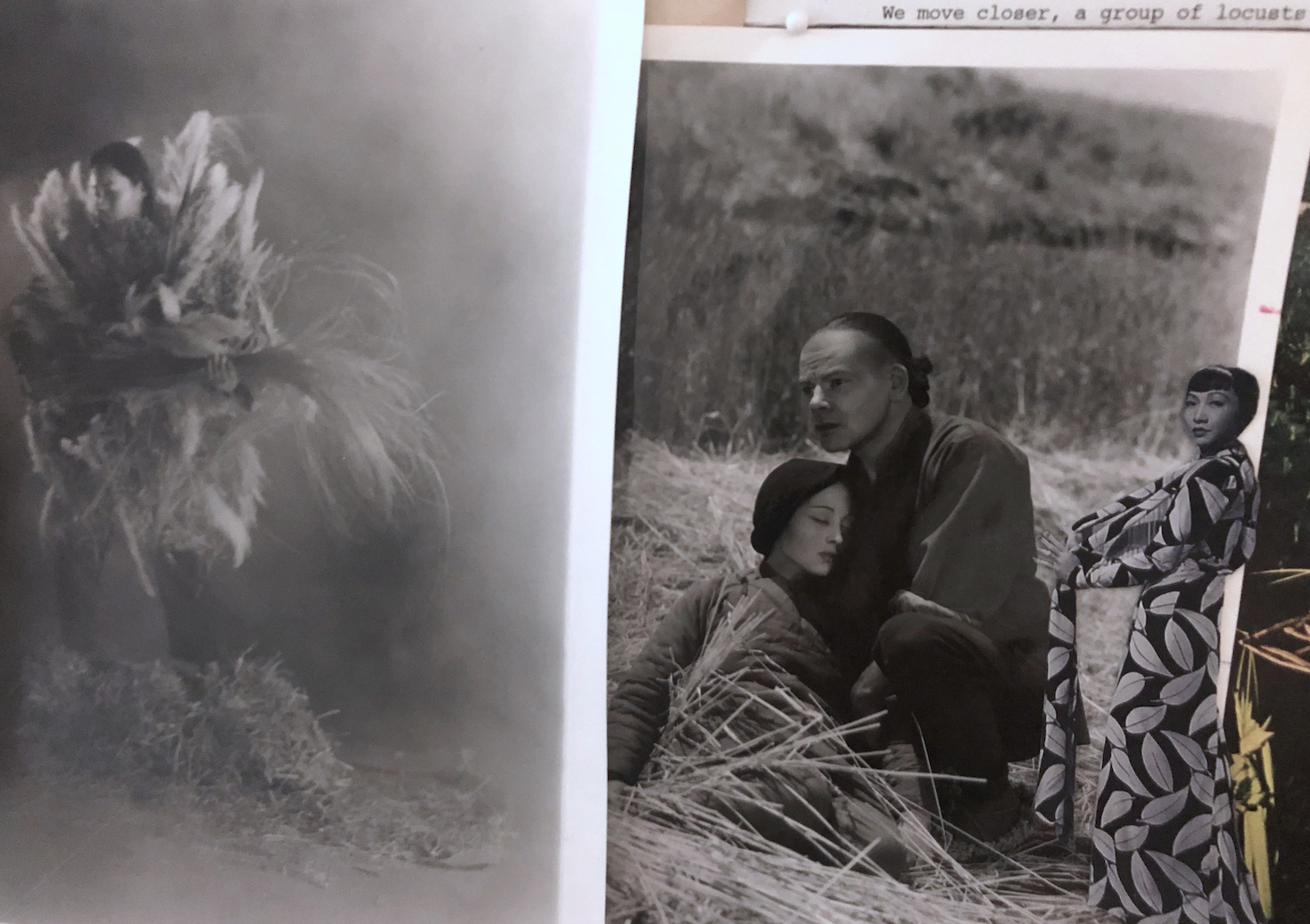

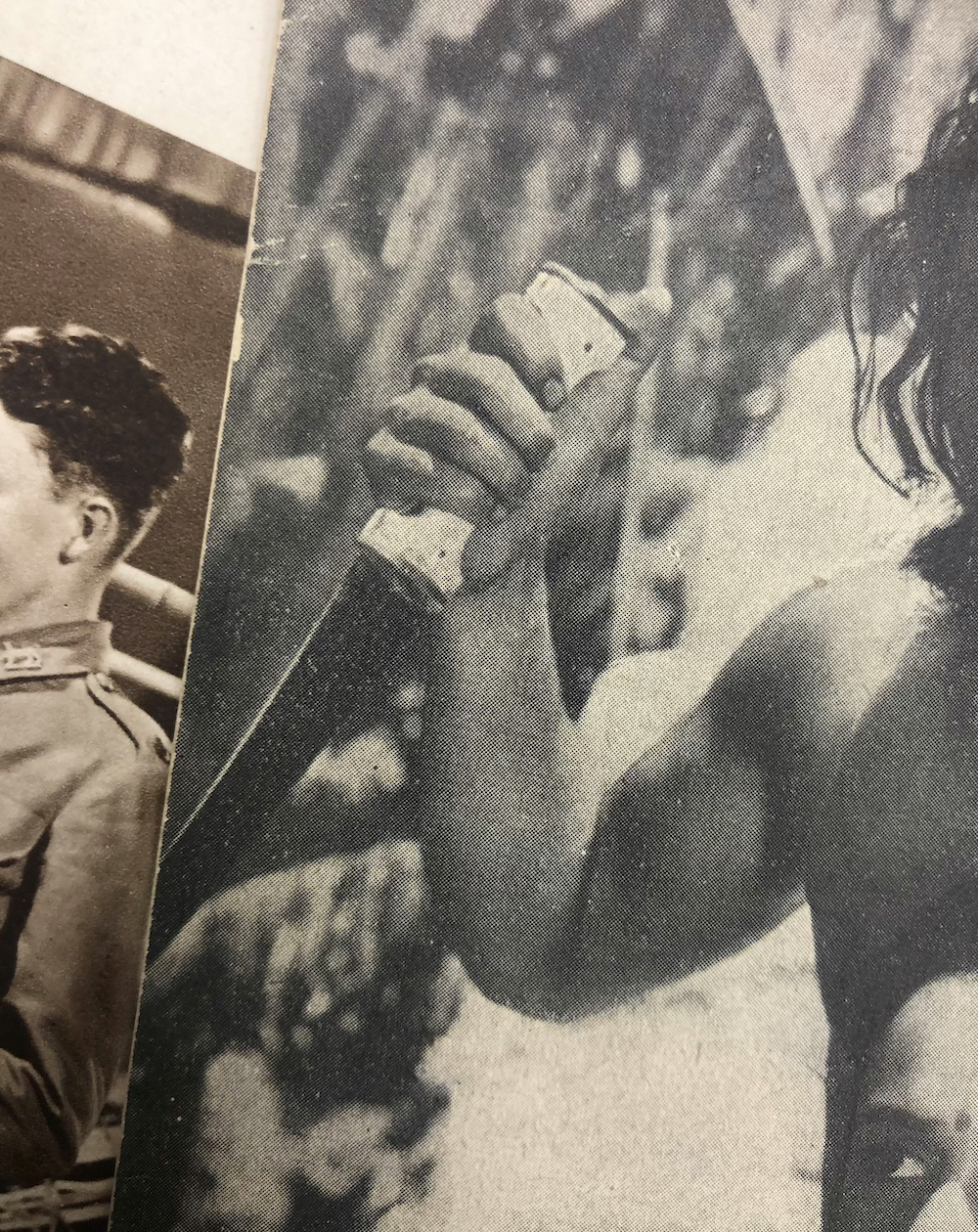

Sabu, 2022. Courtesy the artist © Michelle Williams GamakerConceived as a mode of “fictional allyship” with the marginalized actors of British imperial cinematic history, Michelle Williams Gamaker’s forthcoming film Thieves revisits roles played by the Chinese American actor Anna May Wong and Indian-born American actor Sabu in two twentieth-century fantasy adventure film classics of the same name: The Thief of Bagdad (1924 and 1940).

Thieves sees Williams Gamaker develop a fantasy narrative of solidarity between Wong and Sabu, whose careers were shaped by industry racism and the censorial prohibitions of Code-era Hollywood. Wong’s silent casting in Raoul Walsh’s black-and-white film and Sabu’s sidekick status in the Technicolor version (a multi-directed film, which included British director Michael Powell) challenge the terms of agency and stardom when the only available roles to postcolonial subjects were largely denigrating in form. Focusing on new working dynamics and narrative turns created by its cast, Williams Gamaker opens the desires and realities of the imperial project to a critical reworking of cinematic history.

Thieves is presented here in pre-production and is accompanied by a conversation between Michelle Williams Gamaker and curator Gabe Beckhurst Feijoo.

Gabe Beckhurst Feijoo: Let’s start with your interest in the archive of British and Hollywood studio films made in the context of empire. The films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger have greatly influenced your own. When did you first encounter their films?

Michelle Williams Gamaker: It started with looking at the films I watched in my early teens. Though I didn't go to the cinema, I received a strong cinematic education through TV at home. This is complicated by the fact that when I was younger, I was often left to my devices with the television as a co-parent. By the time I was in my early teens, the BBC used to have these curated programs called the Saturday Matinee, and I just started to watch these incredible Technicolor classics that were highly melodramatic, very much dealing with a western gaze and looking at colonized spaces. I didn’t have the vocabulary to make sense of what I was watching, but I did know that it was something that I recognized, maybe even from the trips that I would take with my mum to Sri Lanka. Or there was something like in Powell and Pressburger’s Black Narcissus (1947) that seemed like the heat that I'd experienced being away. At that age I didn't know the term “brownface,” but I could see that there was something wrong with the casting. I was also aware that there was something I needed to connect with because there was a paucity of representation of brown characters on screen. I latched onto this mode of fiction and loved it on a level of cinematic joy. My dad pushed more Powell and Pressburger my way after coming across Black Narcissus and I fell in love with the directors’ oeuvre.

GBF: Thieves is part of a series of short films developed within the framework of what you call “fictional activism.” Your wider project includes The Bang Straws (2021), a work that reframes the production history of Sidney Franklin’s The Good Earth (1937), one of cinema’s most notorious cases of casting discrimination. Why did you develop this method?

MWG: In 2014 I moved back to London from Amsterdam and there was a marked shift in my writing. I was trying to find a way to write a complex South Asian figure because I was interested in the casting of the character of Kanchi, the lower caste dancing girl from Powell and Pressburger’s Black Narcissus, who is played by the actor Jean Simmons in the film. I wanted to make sure that I could write a politically complex figure that was vocal in the original 1947 character. Simmons is a white actor who plays Kanchi as silent, lascivious, and exoticized, and that seemed completely redundant in 2014 when I began filming. At that time, many of my performers and students were articulating their experiences of gender fluidity and non-binary subjectivity. I knew that I had to cast a South Asian individual who could speak this politicized language.

“Fictional activism” was a term that was applied retrospectively. It’s become a catchall to talk about an individual who has the capacity to self-define through their representation. That's partly to do with my writing, which seeks to address historic injustices through film representation, but it’s also about an injustice that still exists today for actors of color. How do we write a more nuanced position? I don't wish to only make them into heroes. I think complexity means that we can experience all their character positions––the good and the bad, the unreasonable and the envious, the longing and the hurt. Thieves is an evolution of fictional activism because we move now to this space of revenge.

GBF: In the shift to “fictional revenge” you move towards an active form of reprisal. Can you tell us more about this?

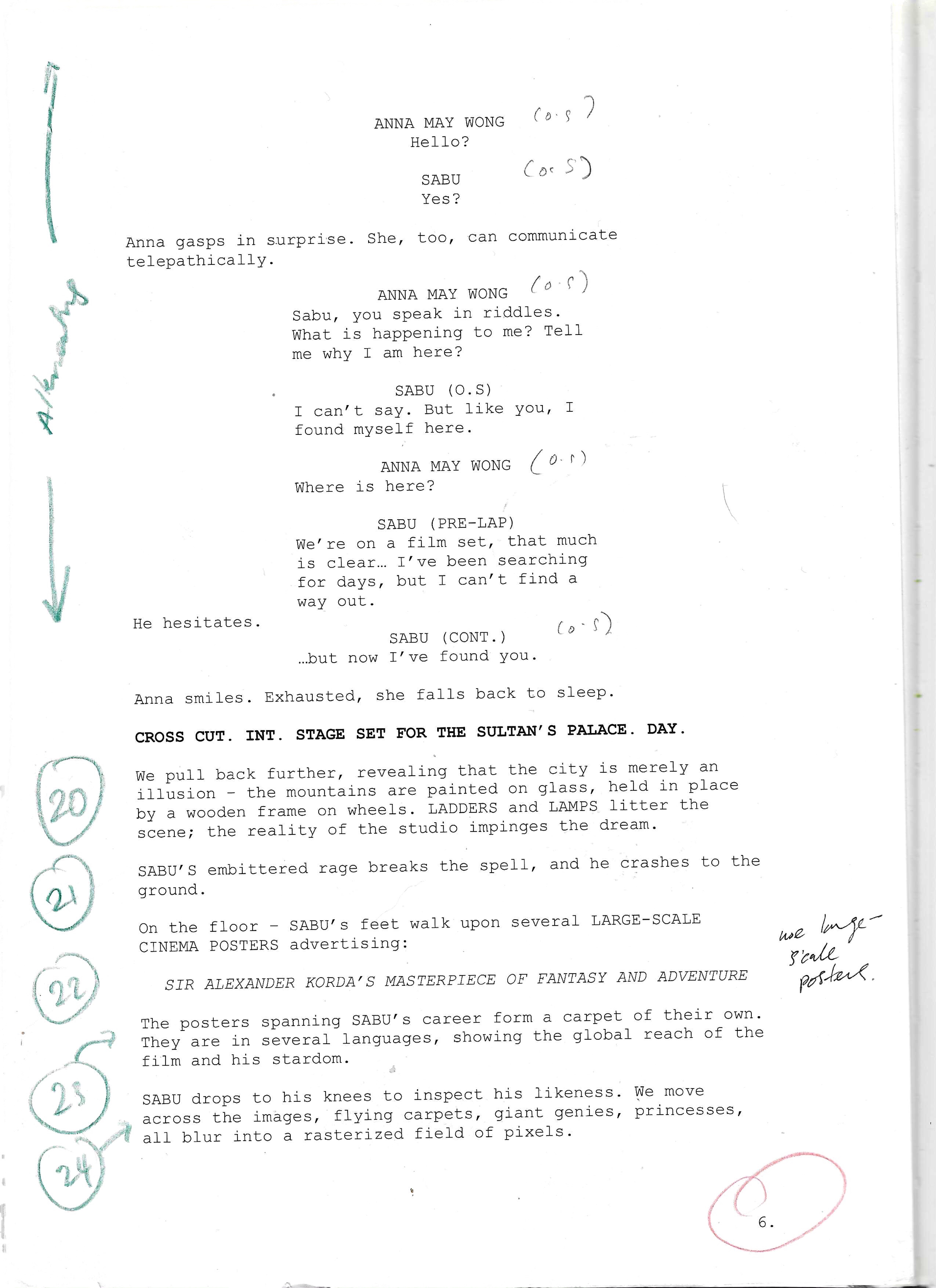

MWG: Between 2014 and 2021 I made the Dissolution trilogy. I was heavily influenced by working with Krishna Istha, who is non-binary. We went from Krishna performing the character of Kanchi (in House of Women and The Fruit is There to be Eaten) to performing the character of Sabu (in The Eternal Return), both of whom were marginalized in Black Narcissus. When I started thinking about the casting discrimination against Wong, I worked with a Chinese performer Dahong Wang. Serendipitously, Anna May Wong starred in the 1924 version of The Thief of Bagdad and Sabu in the 1940 version. This led me to explore how the two protagonists could potentially unite in a new film as allies. By the end of The Bang Straws, I realized that I needed to push the agenda to a more urgent space. I felt as though their agency required more than just a demand for something, it would need to embody and physicalize this demand. Eventually, I’d like my films to move towards “fictional healing” but first, I want blood and revenge.

GBF: The postcolonial and transnational solidarity between Wong and Sabu in Thieves draws on forms of collective action that have emerged through labor movements, from the gherao performed by the “Annamaytons” (a crew of actors that resemble Wong and participate in the overthrowing of the director), to the accountability of the set workers. How has this research exposed you to labor movements within this cinematic canon?

MWG: I wasn't fully aware of this until I started writing the script for Thieves, but the film set is this incredible space that has an imposed hierarchy from the supposedly “low” runner and set constructor to the elevated position of the director. If you read Michael Powell's autobiography, he speaks a great deal about the film set as this great leveling space. I would question this, but thankfully, Powell does think about the solidarity involved in people working towards his vision. I was interested in the question of how to show the set workers and their invisible labor, and how to look at transnational labor movements like union protests on the ground. I learnt about the gherao when I was making the film Colony with Mieke Bal in 2006, which we shot in Kolkata. We made several interviews as part of this film including with the protesters of union movements from the 1960s and 1970s. Gherao is a Hindi word and one I’ve always remembered. With labor ending up as a central subplot in my script, the term resurfaced.

GBF: Shadowy labor practices loom large in British and Hollywood studio films between the 1920s and 1960s. The 1940 version of The Thief of Bagdad features dock, crowd, and court scenes which would have entailed large casts. Beyond the principal and supporting roles, there is the concern in Thieves for all workers on set, particularly those whose labor was less valued or not even documented.

MWG: Some of Powell and Co's version of The Thief of Bagdad was shot in the UK but most of the film was shot in the US due to the outbreak of the Second World War, so I would be fascinated to understand the casting of extras in both contexts. In Black Narcissus, the extras were apparently from the Rotherhithe docks, so they would have likely been first-wave migrant workers. If you look at the clustering of extras, the cast is multinational. In this way, Powell and Pressburger's films actually evidence the global citizen in a way that a number of films may not have, in particular in A Matter of Life and Death (1946). But often, the casting of the extras just serves a need for brown or black bodies.

From a London perspective, the city’s history of former colonized workers and Commonwealth workers arriving through the dockyards and port cities would have provided a prime casting net for directors, I imagine. When you look at Hollywood films even into the eighties, Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), for example, the cast of extras are from Sri Lanka, not from India––it’s a nebulous South Asian diaspora that's being drawn upon. But you can hear Sinhala spoken by the extras in the background. The performers reveal this by simply being themselves, but it doesn't come through the directorial decision because these details don’t seem to matter for the extra. I would really love to focus on the plurality of the extra one day!

GBF: Yes, the script for Thieves identifies several regional British accents.

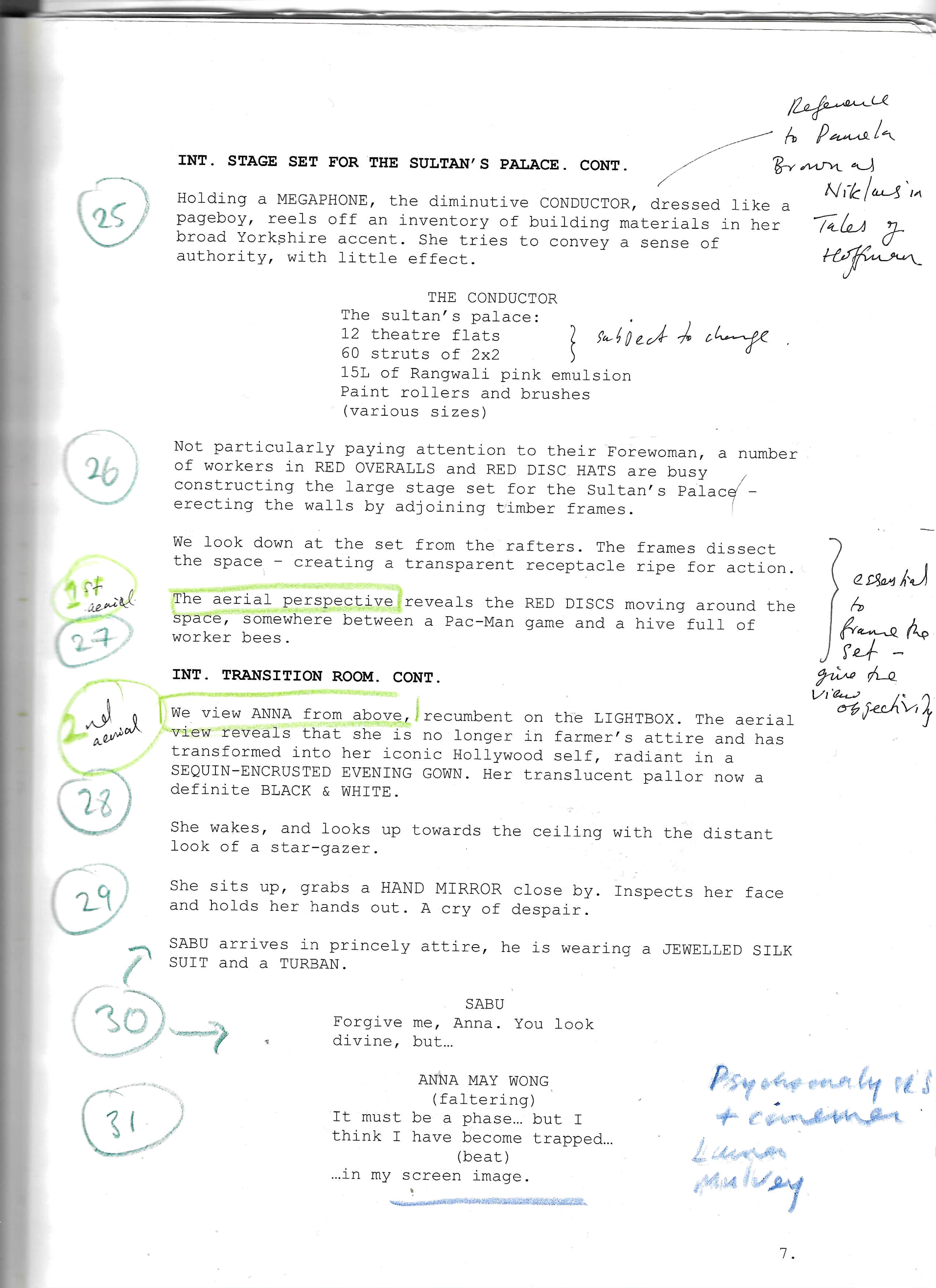

MWG: That’s to stay true to my casting and to my actors. In Thieves, the role of the Conductor will be played by Lucy-May Orange, who is in my film Encore (Resurrection Manifestations) (2018), and is from Yorkshire. Catherine Lord, who appears in several of my films, is from Lancashire. I think part of this is also a conversation around working-class dynamics and the North. My dad is from the North of England and regional divides between the South and the North continuously ostracize workers to this day. I like thinking across the complexities of transnational diasporic cultures and regional cultures.

GBF: Regionality is indicated in the script but not discussed dialogically, and yet these particularized speech acts defy the synonymity of a “neutral” southern English accent with Britishness. These distinctions call up what the scholar Hazel Carby has framed in her telling of the spaces between Black and British, as the question of how subjects become (rather than are) British through the criterion of citizenship, which is deeply meritocratic. On a deeper level, they also activate national and transnational scales of diasporic history.

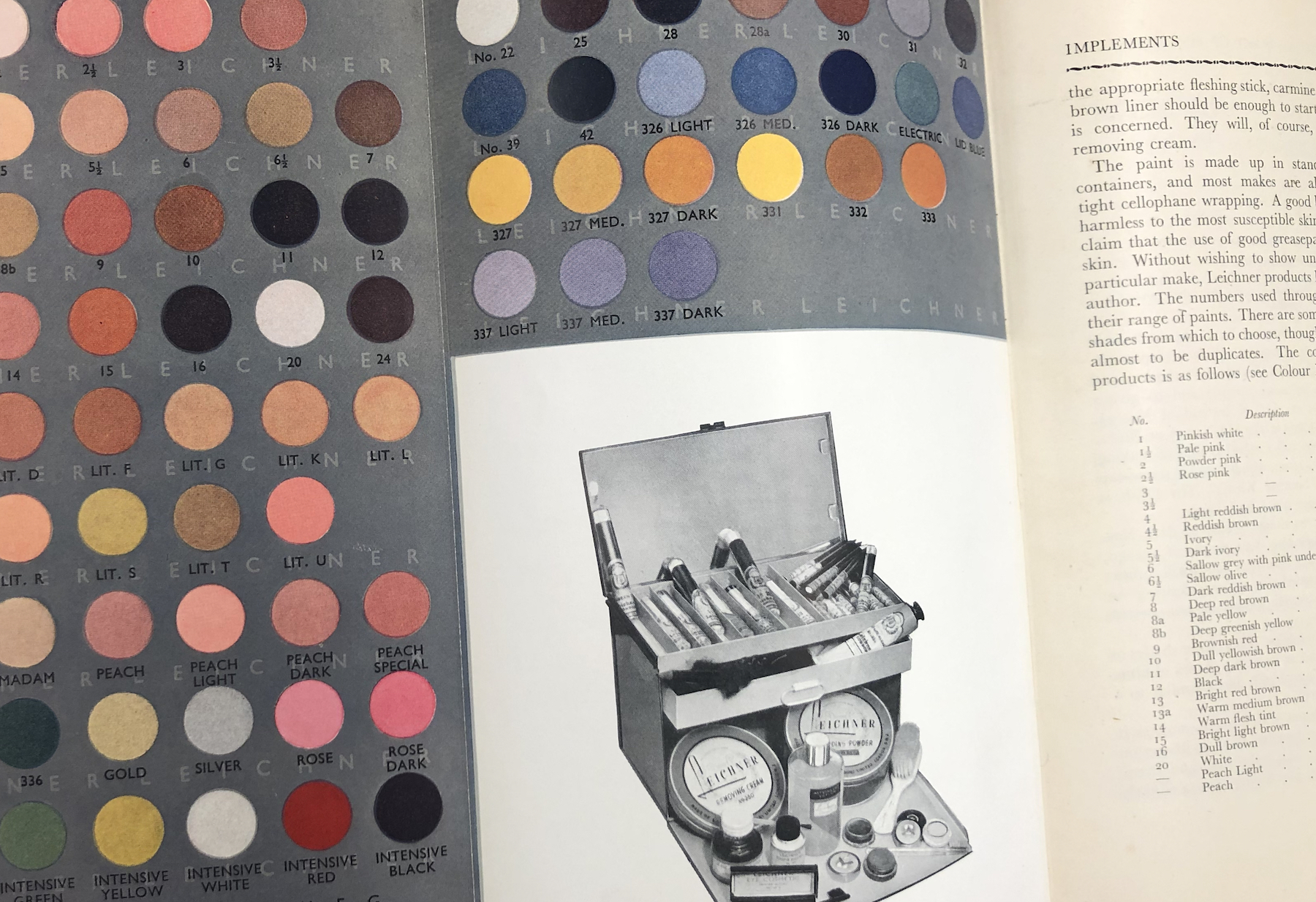

MWG: It’s also a way of revealing the absurd nature of the racist makeup. The makeup is shocking on one level, but it is also ridiculous to reveal that the actor behind the painted surface is from Lancashire. Catherine Lord will be playing the Sultan and I'm not bogged down in gender in that way. Catherine has played Tom Arnold, the circus impresario before, and enjoys playing fluid roles, and that fluidity can also be found in Powell and Pressburger’s films as well as in theatre.

GBF: How do your strategies of re-enactment engage the future? I’m thinking about whether this cycle of films could alter patterns of consumption in time. For instance, in the happenstance of someone going to watch the Thief of Bagdad and finding Thieves instead, your intervention would suddenly become much larger than the environment in which you made the film.

MWG: I would love the films to have their place not only within film festivals or galleries but within a wider popular consciousness. I'd like to hope that it does something I am writing about around the idea of narrative reparation, or how we can use fiction, which has done a lot of damage around the construction of identity, self-worth, and representation, to heal or be involved in a conversation that enables an alternative reading. I would love it if somebody arrived at my film first and then tracked backwards. I can't make that claim because I know that I make quite experimental films and that can sometimes place limits on who your audience is. But I'm hoping that my films start to sit in multiple spaces. I feel more confident about that after slogging for the last eight years on this fictional activism project. I'd love it if they make it onto television––that would be the ultimate thrill, even if it was programmed at 11 pm, it would have started with TV and had made its way back to TV.

GBF: Thieves uses certain structures such as the audition or the script as narrative conceits––and the latter is a form you have used across your work, including Knees and breasts are mountains; The art school reimagined (2021), realized through the UAL Decolonising Arts initiative, where you used the script to present research. What does the script enable for you, as a form of writing or enunciation that also structures artistic contributions?

MWG: I've been experimenting with the script for some time, sometimes trying to transform a gallery into a space for fictional encounters, to read the script within the gallery and to actively draw attention to its infrastructure. The script has become this place to start to penetrate what a structure might look like. It's also a way to write from the experience of the character because dialogue enables this. With scripts––being efficient isn’t quite right––but you must craft what you want to say succinctly. It enables a zoning in on the politics of the work. I also realized that, particularly for actors of color, the casting process presents a very complicated moment. Certainly, if we look historically, the number of abuses and challenges that individuals of color would have faced just in performing makes me address this in my work: what does it mean to perform and what does it mean to make?

The casting space has been a mirror of my own experiences as an artist and its very real glass ceilings. Casting is a form of gatekeeping. It's been very cathartic to speak to my own lived experience through the avatar of my performers. Yet, I find the script to be a very fruitful space. It enables me to be more transparent when I do share the projects. I really think that I had so many questions as a younger artist-filmmaker to my tutors, like, “how does this all get made?” The answers were never forthcoming. It was always like, “Oh yes, you know,” it got very easily lost into some other thing. I don't think a younger filmmaker would find that fudging of how useful (or acceptable) anymore. They deserve to unpick a script and think through how their practice might sit alongside other crafts. Script writing is not for everyone, but because I've been so interested in cinema, I've probably spent a lot of time imbibing some of their mechanisms, and I find it invaluable as a blueprint for my ideas.

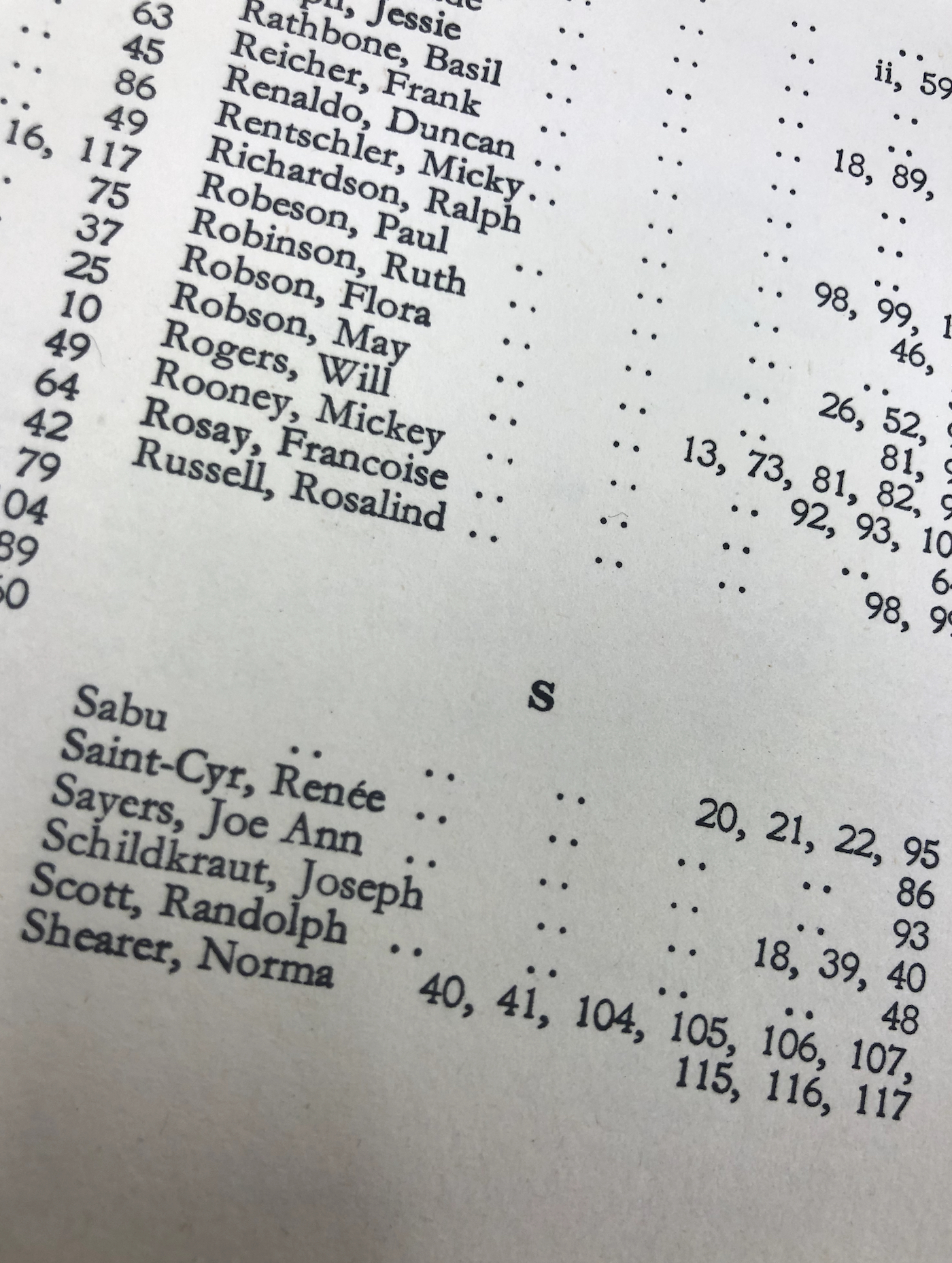

GBF: When did your interest in Sabu begin, and how do you relate to his mass appeal as an actor and character, given his trajectory to fame?

MWG: My early access to Sabu was through two films: Black Narcissus (1947) and The Jungle Book (1937). They were two key performances that in later years I began to see just how much he achieved in his career because he really had international fame. But of course, you soon realise how quickly he gets typecast. He was a child star playing Toomai in Alexander Korda, Robert J. Flaherty, and Zoltan Korda’s 1937 film, Elephant Boy, however, I would argue that Sabu is animalized and infantilized throughout his career. He's always “Sabu, the Elephant Boy,” even into his adult life. He was always this bare-chested body, a beautiful figure of physicality that is also deeply problematic. By the time he is older, the studios didn’t want him anymore. He could not remain an eternal boy and so he gets cast off into C-list movies and eventually ends up working in a Hackney circus and with elephants again, which is how Flaherty came across him as the son of a Mahout in Mysore, India. Flaherty is interesting because he was the anthropologist that made Nanook of the North (1922), a documentary famous for fictionalizing documentary moments. In Nanook, you see entirely staged moments authentically passed off as traditional Inuit life. But when Sabu got the role of Toomai in Elephant Boy he was sent to the UK to learn English. He later became an American citizen when he moved to the US.

GBF: Can you speak about the role of memorabilia as source material and what it means to redistribute a complex material culture?

MWG: I've been slowly collecting Sabu’s movie ephemera because his image is completely dispersed, and I want to piece together this man with some level of active care and to put it all back together as best I can. In 2018, I went on a pilgrimage to his grave at The Forest Lawn Memorial Cemetery in LA. After twenty years of practicing as an artist, more opportunities have started to come my way in the last few years, but I absolutely felt a limitation and I wanted to speak to Sabu about this. It was a genuine moment of shedding tears and talking across the decades about our mutual frustrations with the industries we worked in. I went to a thrift store and bought a brown taffeta eighties cocktail dress. I had gold stiletto heels, and I painted my toenails and fingernails gold and just sat with him dreaming I was a Hollywood starlet. Then there was this moment where the security guards came up to me because I had a camera rolling, of course, and they were like “mam, what are you doing?” And I was like, I am not stopping this camera, I’ve come too far, so I just blurted out, “It’s just that I'm a distant relative.” This phrase became the name of a solo show at Tintype Gallery in London in 2019. This idea of fictional kin is interesting to me on a number of levels, partly because I think that for anybody with a history of migration or belonging to a diaspora, there are so many gaps in the records. Fiction becomes a tool for compensating for absent legacies. I'm not the first person to say this––there are so many black feminist writers who are using fiction to fill the gaps. I'm learning from them all the time, but in my own way, that's what I'm doing too. I’m creating an imaginary allied network.

GBF: It’s also a reparative relationship to fiction where the genre has caused so much harm.

MWG: Precisely. How do you turn fiction in on itself so that it now does our bidding and doesn't inflict further damage? As Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak asks, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” ––can we talk back to something? We absolutely can, of course. But I propose it is by using the tools that were so damaging against itself.

A concept that has been influential to me in this respect is “fandom as methodology” developed by Catherine Grant and Kate Random Love, which was very helpful for thinking about how writing can bring you closer to your fandom. Through this concept of fandom, I realized that all my so-called fictional activists are like allies or fictional kin, and they offer lots of fruitful possibilities to say something that I couldn’t articulate around the harm of this lack of representation.

GBF: You’ve often cast directing and production roles as characters with speaking parts, from that of The Voice Coach in The Bang Straws to Powell himself. They are tasked with performing.

MWG: There's also the anonymous reader in House of Women who embodies the crisp, cold voice of authority. I think they're all there to somehow embody the structure in different degrees. I'm nervous about portraying Powell, because he will be known in the imaginary. But I think it's something to do with allowing my characters to have something to resist against or to react with. I've always been very transparent and grateful to work with quite a diverse film crew. But who gets imaged often are the white laborers, the cinematographer and the focus puller, so I cast them as well to intentionally make a point of this. But for Thieves, I would expect that my workforce will embody a very broad pool of people and they don't have to be from a past. That means that we needn’t be faithful to 1930s or 1940s Hollywood.

There's a film that is important to me and which feels relevant here and that's Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel (1962). In the opening sequence, the workers–– serving staff, waiters, butlers––protest by downing their tools and leaving the room. The bourgeoisie are left behind and are forced to have their dinner party without being served. What happens is that they're in the trenches of this class malaise where they can't leave the dining area and cannot cross the threshold. They're effectively trapped in their own class and space. It becomes horrific and there's even a moment of cannibalism. But it’s due to the workers downing their tools that change is forced upon the hierarchal structures that have calcified a way of working. I think the Buñuel film is an important exercise in trying to see what would happen if the work behind the scenes enabled something else to take shape.

GBF: You can feel the influence of this scene on Thieves. In the script’s closing scene of the cast’s rebellion, the film threatens to fall apart without collective participation. The director’s vision cannot sustain the fantasy alone.

MWG: It’s complicated because I'm not trying to take Powell down, what I want to do is be critically affectionate because I'm a complete admirer of his and Pressburger’s body of work. But there has to be a moment when all filmmakers are accountable for the work they make. If you love something enough, you should be able to critique it and they should be able to hold it. I know he doesn't get a real right of reply, but I hope that the writing enables a conversation. Very crucially, Powell isn’t killed in the script, he's held hostage and he's asked to answer something, but he's not wiped out or cancelled. He has to see that there's a repercussion to his fictional whims. I'm interested in what happens if we do hold people to account. It's going to be something that the actor Mark Gillis (who will play Powell) is reading in Powell’s autobiography at the moment––and together, we're going to go deep into the psyche of the Director.

GBF: The demand for these films isn’t waning, but there appears to be an appetite for critical interventions. The BFI in London have announced a Powell and Pressburger season for 2023, and you’ve been asked to present some of your work.

MWG: I like the notion of a vibrational hum between these worlds. I’ve also had the pleasure of having my work curated in a double bill with Black Narcissus. House of Women was the intro film and I loved that. With Thieves, the idea of showing the Sultan in brownface and the prosthetic nose is about naming it and seeing it for what it is. Because it was absorbed into the cultural imaginary prior to a more critical audience, it was understood as just the way it was done. I'm sure some people questioned it, but there was no forum in which to raise these questions. So, this film will go to the source of a lot of very uncomfortable spaces and I'm hopeful the production can hold this.

Michelle Williams Gamaker’s film trilogy Dissolution (2017–19) can be viewed in full on MattFlix here.

© 2022 8th Triennial of Photography Hamburg 2022 and the author; images the author's own unless otherwise stated.